You're Being Lied to About Your Menstrual Cycle

The follicular phase isn't the high-estrogen state you think it is, while the luteal phase is often characterized by the highest estrogen levels.

Disclaimer: Content for entertainment purposes only. Not medical or health advice.

It’s absurd how misinformed most women are about their menstrual cycle. But it is not these women’s fault. Accurate information about how the female body works can be surprisingly hard to find. In my opinion, the crux of this confusion is the very misleading representation of how exactly our hormone levels fluctuate throughout our menstrual cycles. These misrepresentations are sadly shared by most medical/biology textbooks, online fertility articles, and books written by “fertility specialists” alike.

A correct understanding of how exactly our hormonal levels change throughout the menstrual cycle, and how these changes affect us physically and mentally, is crucial to ensuring good health and quality of life.

To start dismantling these misrepresentations, we have to start with the biggest one: the belief that PMS is caused by progesterone and that estrogen levels are highest in the follicular phase.

PMS Is Not Normal, and It Is Caused by Excess Estrogen

The “Premenstrual Syndrome” entry on “StatPearls,”1 which is an online healthcare education resource for health professionals, estimates that nearly 50% of reproductive-age women worldwide deal with PMS.

However, this figure turns out to be much higher, since most women have been conditioned to accept unacceptable symptoms as normal.

Numerous studies surveying and tracking women's symptoms234 found that in many of the cohorts tested, 80-90% of all reproductive-age women experience some degree of PMS symptoms, with reports of over 98%5 of women from certain cultural, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds experiencing PMS. Of those, over 50% of women report their symptoms to be either “moderate” or “severe” as opposed to “mild.”

As expected, the reason why many “official” figures are lower is because many women don’t report PMS symptoms that they view as “the normal amount of PMS.” Due to the normalization of PMS symptoms, women don’t realize that the actual normal amount of PMS symptoms…is zero.

PMS has multifaceted and often hellish manifestations. Symptoms such as tender, swollen breasts, digestive disturbances, nausea, migraines, acne and water retention and the exacerbation of autoimmune conditions, epilepsy, mood disorders, anxiety, allergic reactions, eating disorders and substance abuse are only some of the symptoms that many women are faced with in the week (or two) before their menstrual bleed.

Women suffering from PMS tend to feel their worst after ovulation, in the luteal phase, which is the latter half of their cycle. In a woman with a regular, ovulatory, 28-day cycle, the luteal phase should last two weeks, starting just after ovulation (which often happens on day 14 of the cycle, but not always), and ending around day 28, just before the onset of the menstrual bleed. This is the time when hormonally-driven negative symptoms are amplified.

Some women experience symptoms so severe that I have more than once heard the phrase “Women are meant to feel well only one week per month.” For most women, this “good” week happens during the follicular phase, the first half of their cycle.

PMS symptoms are classic signs of estrogen excess, yet women are told that estrogen is highest in the first half of their cycle when they feel their best. This contradiction puzzled me until I realized that misleading data and poor research practices have led women (and certain health authorities) to accept the following incorrect assertions as fact:

The follicular phase (the first half of the menstrual cycle) is a phase of high estrogen.

The luteal phase (the second half of the menstrual cycle) is a phase of low estrogen.

Increased progesterone in the luteal phase is what causes PMS.

Again, this is incorrect, and I will provide data to support this.

I find this information to be insanely important to bring awareness to, as whether it is you, the reader, suffering from PMS, or whether you have a girlfriend, sister or friend suffering from it, PMS often fails to be properly addressed. The lack of less invasive treatment options for PMS (largely due to misunderstandings about its etiology) leads many women to hysterectomies/oophorectomies (the surgical removal of the uterus and/or ovaries to stop the menstrual cycle entirely) or hormonal contraceptives (which act akin to chemical castration by fully suppressing the ovaries’ ability to release hormones).

To solve the problem, we must first correctly identify it.

The Follicular Phase is Not a Phase of High Estrogen

Many health publications, such as the one below, claim that PMS is caused by declining estrogen levels after ovulation. However, this isn’t true.

“Changes in hormone levels are thought to be the main cause of PMS/PMT. More specifically, it is the decline in oestrogen and rise in progesterone for up to two weeks before the period starts.”

- https://thesurreyparkclinic.co.uk/gynaecology/conditions-treated/premenstrual-syndrome/

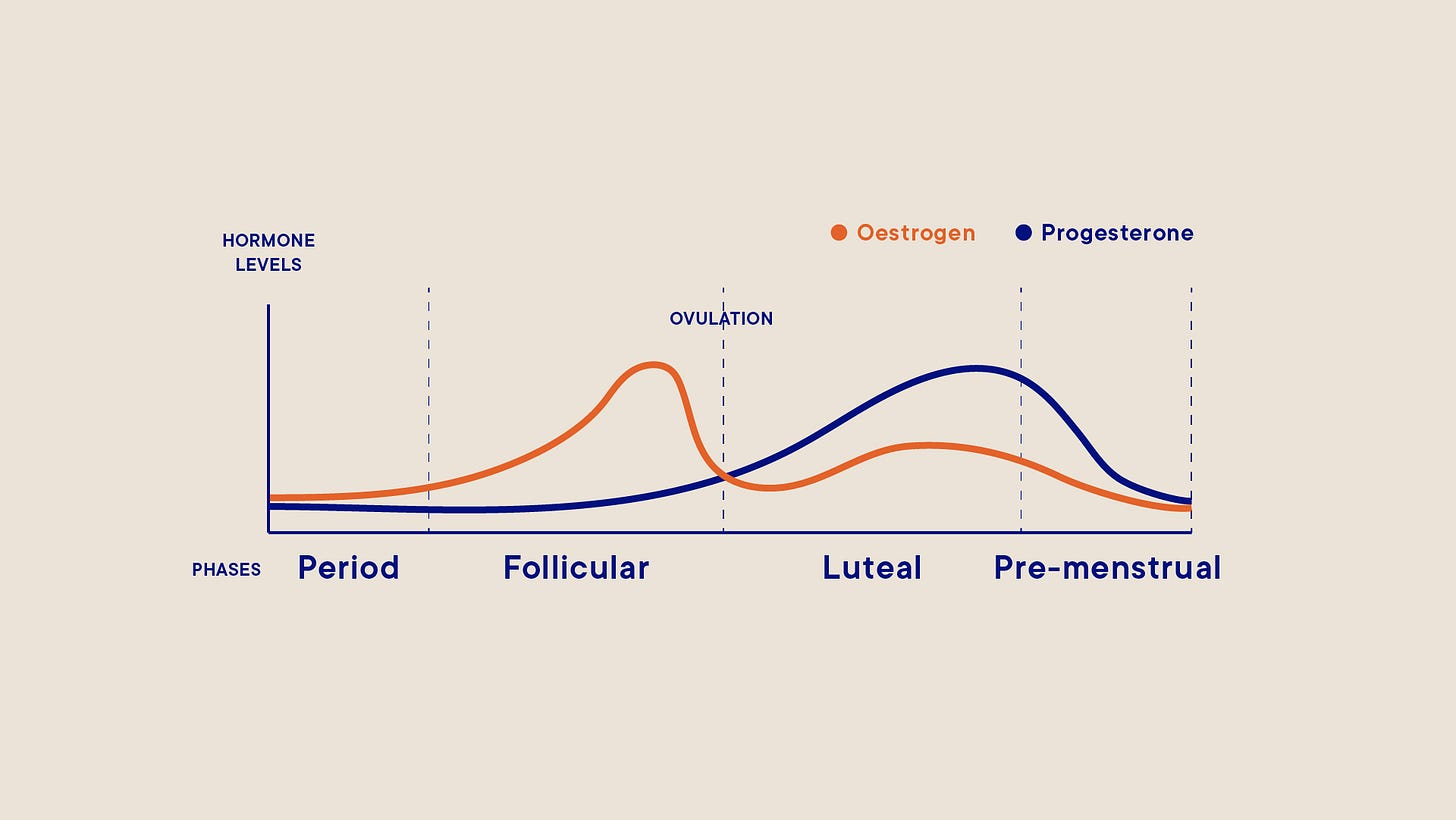

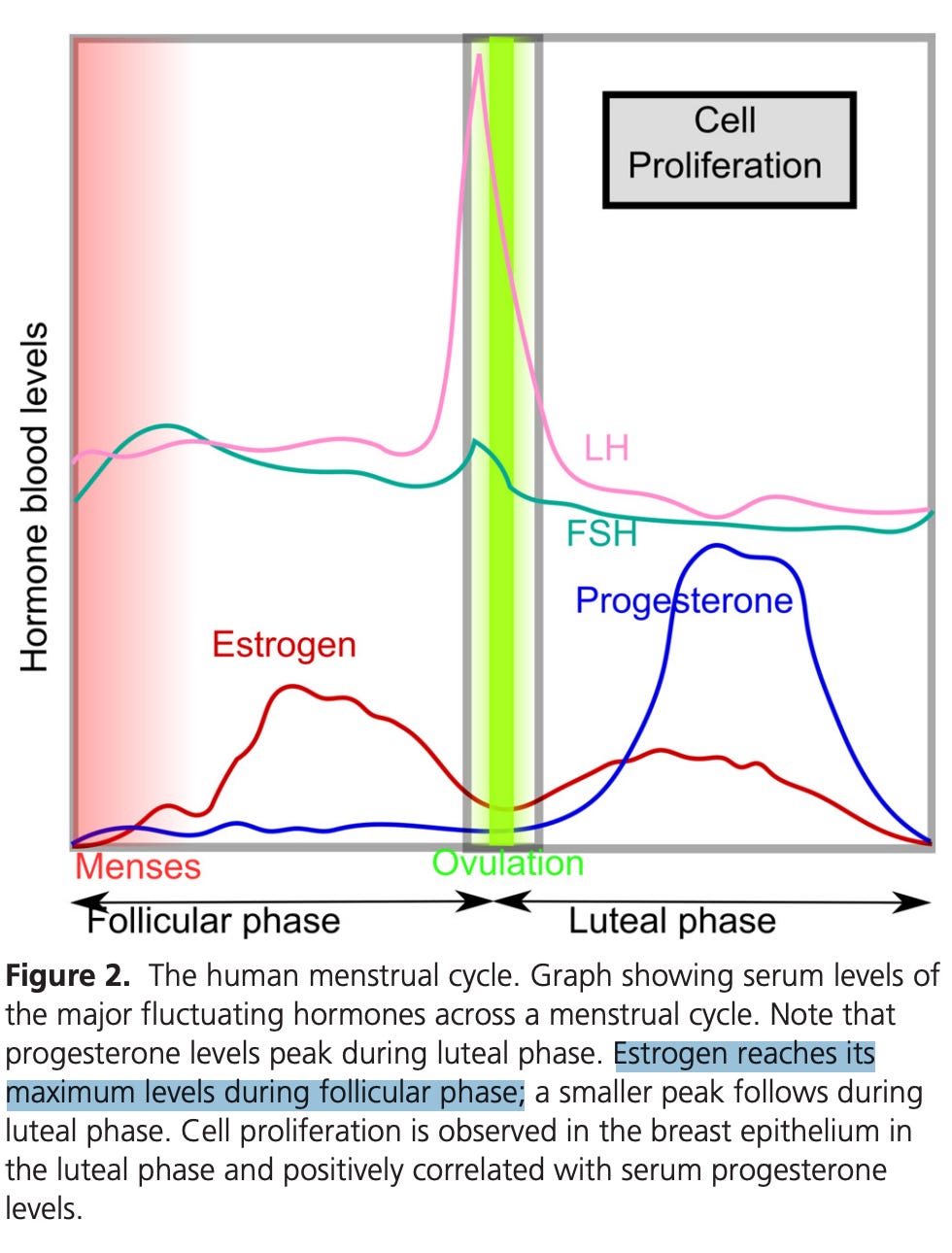

I think every woman has seen the menstrual cycle graph that looks something like this:

“Estrogen reaches its maximum levels during follicular phase.”6 🤔

The above graphs come from respectable medical journal publications. The common menstrual cycle graph shows estrogen levels being high in the follicular phase, peaking at ovulation, and decreasing after ovulation while progesterone rises. This is only partly true. While progesterone levels should rise exponentially after ovulation, estrogen levels do not decrease; they stay elevated or can increase further.

Data shows that, across a regular, 28-day ovulatory cycle, estrogen levels can be 6x higher in the luteal phase than in the follicular phase.

This is why symptoms of estrogen dominance are more pronounced in the luteal phase (the latter half of the cycle).

Data Supporting High Estrogen Levels in the Luteal Phase

One 2005 study7 of female cyclists with regular menstrual cycles, in their early to mid-twenties, found their estrogen levels to be:

Up to 264 picomoles per litre in the early follicular phase

Up to 1328 picomoles per litre at ovulation & during the luteal phase

The study looked at both trained and untrained female cyclists, measuring their sex hormones during the early follicular phase, ovulation (late follicular), and mid-luteal phase.

In the study, "late follicular" refers to ovulation, meaning that from ovulation onwards, women tend to have higher levels of estrogen.

Some of the participants in the untrained sample had higher estrogen levels in the luteal phase than at any other point in their cycle, including ovulation. Once again, women are taught that ovulation is the time in their cycle when their estrogen levels are at their peak. Yet, for many, this may not be true.

In the untrained sample, the highest estrogen concentration observed in the luteal phase was 1613 picomoles per litre, while the highest estrogen concentration observed at ovulation was 1118 picomoles per litre.

If we graph the average recorded estrogen levels and the highest recorded estrogen levels for each part of the cycle in this study (for the combined trained and untrained groups), this is what the graphs end up looking like:

This is in stark contrast to the graphs found in fertility textbooks and publications alike which show estrogen being high in the follicular phase and dropping in the luteal phase.

Another study8 of 12 women with healthy cycles found that estrogen levels ranged from 83.3 pmol/l to 171 pmol/l in the follicular phase, and from 341.3 to 1040.3 pmol/l in the mid-luteal phase, a nearly tenfold increase in estrogen for some women.

Yet another study9 tracking 60 women with self-reported healthy, regular menstrual cycles for two months found similar results, with estrogen levels higher in the luteal phase than in the follicular phase. The measurements were taken during week 1 of the cycle and again 8 days after a positive ovulation test.

These findings are in stark contrast with traditional menstrual cycle graphs, which show estrogen being high in the follicular phase and dropping in the luteal phase. Yet, schools still teach girls that it’s the follicular phase that’s a phase of high estrogen, leaving them confused and wondering why their symptoms of estrogen dominance happen later in their cycle.

A more accurate graph would show both estrogen and progesterone levels being lower in the follicular phase and higher in the luteal phase.

“The follicular phase is a time of low steroid production by the ovary, until near the end of the phase, just before ovulation, when estrogen rises. The luteal phase is a time of high estrogen and high progesterone synthesis. Many publications describe the follicular phase as a time of high estrogen, and the luteal phase as a time of low estrogen, roughly the opposite of the actual situation. And an even larger number of studies get the results they want by using a short exposure to estrogen to study something which takes a long time to develop.” – Dr. Ray Peat, Article: “Aging, estrogen, and progesterone”

With estrogen concentrations being so much higher in the luteal phase, estrogen dominance is more pronounced in the luteal phase, and this is what causes women to suffer.

Progesterone Takes the Blame for What Estrogen Does

Since progesterone levels rise exponentially in the luteal phase (or, at least, they should), many have been led to believe that progesterone is the “bad guy,” and the cause behind PMS. However, bioidentical progesterone has successfully treated PMS many times.

Dr. Katharina Dalton, a pioneer in PMS research, demonstrated in her work that PMS is brought on by a deficiency of progesterone or a deficiency relative to estrogen. Her body of work (including multiple books) documents hundreds of cases of women getting relief from PMS after being administered bioidentical progesterone.

In one of her earlier published papers,10 of 61 women suffering from PMS who received progesterone injections, 83.5% became symptom-free.

Ideally, the elevated progesterone levels during the luteal phase should protect against deleterious effects of high estrogen levels. Although both adequate estrogen and progesterone levels are needed for a healthy menstrual cycle, they are like yin and yang. Progesterone acts in ways that are largely opposite to the functions of estrogen, guiding and restraining estrogen’s actions. When the two are imbalanced, estrogen can become destructive.

Estrogens cause tissue proliferation, while progesterone mostly causes differentiation.11 Estrogen causes tissues to retain water,12 while progesterone acts as a diuretic.13 Estrogen can contribute to mental disturbances by increasing the release of cortisol by the adrenal glands14 and slowing the breakdown of adrenaline.15 Progesterone, on the other hand, lowers cortisol levels and attenuates the activation of the HPA axis.1617 Estrogen increases glutaminergic activity in the brain,18 the excess of which can result in nervous symptoms such as nail biting, OCD, body dysmorphia, and ADHD. Progesterone increases GABA, which opposes the excitatory effect of glutamate.19 Estrogen promotes the release of histamine.20 Progesterone inhibits histamine secretion.21

Poor research practices have contributed to the misunderstanding of progesterone’s role in PMS. Low levels of allopregnanolone (a direct metabolite of progesterone), are a known feature of PMS. Yet, research blunders, such as failing to take into consideration the differences in the absorption rate of different routes of progesterone administration, and mixing data from studies using bioidentical progesterone with those using synthetic progestins (the effects of which are more akin to those of the estrogens and androgens, and only partially resemble progesterone’s action) have muddied the findings on the role of progesterone in the treatment of PMS, and estrogen in causing it.

Dietary Support for a Smooth Luteal Phase

Producing enough progesterone in the luteal phase, making sure that this progesterone can bind to its receptors, being able to prevent the over-production of estrogen, and ensuring adequate estrogen clearance by the liver, gut and kidneys, are all dependent on the body having adequate cellular energy.

The production and utilization of this energy are partly dependent on a nutrient-dense diet, adequate in calories, carbohydrates, animal protein, minerals, and fat and water-soluble vitamins.

Poor dietary habits, such as skipping meals, fasting, eating salads as meal replacements, low carb diets and avoiding animal foods, can lower active thyroid hormone levels, needed to release progesterone and support the liver and gut in clearing excess estrogen. Animal protein (including glycine, found in gelatin), dietary carbohydrates, and nutrients like vitamins E, B6, C, and zinc, are needed to produce progesterone and clear excess estrogen. In an undernourished body, PMS thrives.

Dr. Dalton discovered that eating a starch-containing meal every 3-4 hours alleviated PMS completely in 19% of participants without needing supplemental progesterone.22 Progesterone can’t exhibit its protective actions when blood sugar falls too low.

“Progesterone receptors do not bind to molecules of progesterone in the presence of adrenalin, which is released when the blood glucose level is low. While awaiting their first appointment, 84 women with severe premenstrual syndrome (PMS) completed a questionnaire detailing all food and drink consumed on seven consecutive days. The average daytime interval between starch-containing foods was 7 hours, with an overnight interval averaging 13 ½ hours. This suggested that women with PMS might benefit from shorter food intervals between starch-containing foods and avoidance of large meals. On receipt of their questionnaires women were advised to follow a three-hourly starch diet, which was beneficial in 54 per cent with improvement in a further 20 per cent. The diet alone proved effective in 19 per cent, who needed no additional medication for full relief of premenstrual symptoms.”23

Many women under-eat, skip meals, and avoid animal protein and dietary sugars. Combined with exposure to environmental xenoestrogens, phytoestrogens from foods like soy, and polyunsaturated fats (which interfere with the liver’s ability to detoxify old estrogens),2425 the imbalance between progesterone and estrogen in the luteal phase becomes greater, resulting in often agonizing symptoms.

To increase progesterone and balance estrogen levels, apart from eating enough and eating often, consider these foods:

Ripe fruit: Carbohydrates, especially from ripe fruit (with ample potassium and vitamin C) lower cortisol and adrenaline and increase thyroid hormone levels, helping us use progesterone. Citrus fruits, like oranges, contain flavonoids, such as naringin,26 which lower the excessive production of estrogen by body fat stores.

Oysters: High in magnesium and zinc, which help regulate pituitary gland activity, necessary for ovulation and progesterone production. Selenium and iodine in oysters help to make thyroid hormones.

Liver: High in vitamin A, vitamin E, copper, and B vitamins, all essential for progesterone production.

Butter: Butter is a rich source of cholesterol, a primary building block of all hormones. Butter is one of the only foods naturally high in progesterone. One study found that of all dairy products, butter has the highest progesterone concentration, at 130-300 ng/g.27

Raw carrots and well-cooked vegetables: Fiber helps excrete old estrogens and toxins, preventing reabsorption.

Scallops: Rich in taurine, supporting the liver in eliminating excess estrogen.

A2 dairy (such as goat milk): Dairy is a great calcium source, which comes packed with fat-soluble vitamins that help manage calcium in the body. Women given calcium or those on high calcium diets experience less PMS,28 due to the prolactin-lowering effect of calcium.

For those who need extra support, supplemental bioidentical progesterone (such as Dr. Peat’s “Progest-E” or Ona’s Naturals “LunaPro” creams) used throughout the luteal phase can help alleviate symptoms.

I hope this article clarifies why symptoms of estrogen dominance flare up in the luteal phase and reinforces that progesterone is not the villain in this battle.

My Substack is a reader-supported publication. If you enjoyed this article, consider becoming a paid subscriber ($15 per month or $99 for a yearly subscription), to allow me to continue devoting my time and effort to researching and writing.

Paid subscribers get full access to all of my articles and podcast episodes. My other articles dive deeper into topics such as metabolic health, estrogen dominance, and other fertility and health myths we have been taught.

Some of my other articles:

Content for entertainment purposes only. Not medical or health advice.

Gudipally PR, Sharma GK. Premenstrual Syndrome. 2023 Jul 17. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan–. PMID: 32809533.

Chumpalova P, Iakimova R, Stoimenova-Popova M, Aptalidis D, Pandova M, Stoyanova M, Fountoulakis KN. Prevalence and clinical picture of premenstrual syndrome in females from Bulgaria. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2020 Jan 15;19:3. doi: 10.1186/s12991-019-0255-1. PMID: 31969927; PMCID: PMC6964059.

Matsumoto T, Asakura H, Hayashi T. Biopsychosocial aspects of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013 Jan;29(1):67-73. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2012.705383. Epub 2012 Jul 19. PMID: 22809066.

Ababneh MA, Alkhalil M, Rababa'h A. The prevalence, risk factors and lifestyle patterns of Jordanian females with premenstrual syndrome: a cross-sectional study. Future Sci OA. 2023 Aug 8;9(9):FSO889. doi: 10.2144/fsoa-2023-0056. PMID: 37752914; PMCID: PMC10518813.

Ghani S, Parveen T. Frequency of dysmenorrhea and premenstrual syndrome, its impact on quality of life and management approach among medical university students. Pak J Surg. 2016;32(2):104–110

Brisken, Cathrin; Hess, Kathryn; Jeitziner, Rachel . (2015). Progesterone and Overlooked Endocrine Pathways in Breast Cancer Pathogenesis. Endocrinology, (), en.2015-1392–. doi:10.1210/en.2015-1392

Tanja Oosthuyse; Andrew N. Bosch; Susan Jackson. (2005). Cycling time trial performance during different phases of the menstrual cycle. , 94(3), 268–276. doi:10.1007/s00421-005-1324-5

Farrar, D.; Neill, J.; Scally, A.; Tuffnell, D.; Marshall, K. . (2015). Is objective and accurate cognitive assessment across the menstrual cycle possible? A feasibility study. SAGE Open Medicine, 3(0), 3/0/2050312114565198–. doi:10.1177/2050312114565198

Shultz, S. J.; Wideman, L.; Montgomery, M. M.; Levine, B. J. . (2011). Some sex hormone profiles are consistent over time in normal menstruating women: implications for sports injury epidemiology. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 45(9), 735–742. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2009.064931

GREENE R, DALTON K. The premenstrual syndrome. Br Med J. 1953 May 9;1(4818):1007-14. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4818.1007. PMID: 13032605; PMCID: PMC2016383.

Prior, Jerilynn C.. (2020). Women’s Reproductive System as Balanced Estradiol and Progesterone Actions: A revolutionary, paradigm-shifting concept in women’s health. Drug Discovery Today: Disease Models, (), S174067572030013X–. doi:10.1016/j.ddmod.2020.11.00

Stachenfeld NS, DiPietro L, Palter SF, Nadel ER. Estrogen influences osmotic secretion of AVP and body water balance in postmenopausal women. Am J Physiol. 1998 Jan;274(1):R187-95. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.1.R187. PMID: 9458917.

Atallah AN, Guimarães JA, Gebara M, Sustovich DR, Martinez TR, Camano L. Progesterone increases glomerular filtration rate, urinary kallikrein excretion and uric acid clearance in normal women. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1988;21(1):71-4. PMID: 3179582.

Caticha O, Odell WD, Wilson DE, Dowdell LA, Noth RH, Swislocki AL, Lamothe JJ, Barrow R. Estradiol stimulates cortisol production by adrenal cells in estrogen-dependent primary adrenocortical nodular dysplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993 Aug;77(2):494-7. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.2.8345057. PMID: 8345057.

Haoping Mao, Hong Wang, Shangwei Ma, Yantong Xu, Han Zhang, Yuefei Wang, Zichang Niu, Guanwei Fan, Yan Zhu, Xiu Mei Gao, Bidirectional regulation of bakuchiol, an estrogenic-like compound, on catecholamine secretion, Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, Volume 274, Issue 1, 2014, Pages 180-189, ISSN 0041-008X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2013.11.001.

Stephens MA, Mahon PB, McCaul ME, Wand GS. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis response to acute psychosocial stress: Effects of biological sex and circulating sex hormones. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016 Apr;66:47-55. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.12.021. Epub 2015 Dec 24. PMID: 26773400; PMCID: PMC4788592.

Marie Vadstrup Pedersen, Line Mathilde Brostrup Hansen, Ben Garforth, Paul J. Zak, Michael Winterdahl, Adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion in response to anticipatory stress and venepuncture: The role of menstrual phase and oral contraceptive use, Behavioural Brain Research, Volume 452, 2023, 114550, ISSN 0166-4328, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2023.114550.

Oberlander JG, Woolley CS. 17β-Estradiol Acutely Potentiates Glutamatergic Synaptic Transmission in the Hippocampus through Distinct Mechanisms in Males and Females. J Neurosci. 2016 Mar 2;36(9):2677-90. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4437-15.2016. PMID: 26937008; PMCID: PMC4879212.

Kaura V, Ingram CD, Gartside SE, Young AH, Judge SJ. The progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone potentiates GABA(A) receptor-mediated inhibition of 5-HT neuronal activity. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2007 Jan 15;17(2):108-15. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.02.006. Epub 2006 Mar 6. PMID: 16574382.

Bonds RS, Midoro-Horiuti T. Estrogen effects in allergy and asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013 Feb;13(1):92-9. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32835a6dd6. PMID: 23090385; PMCID: PMC3537328.

Vasiadi M, Kempuraj D, Boucher W, Kalogeromitros D, Theoharides TC. Progesterone inhibits mast cell secretion. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2006 Oct-Dec;19(4):787-94. doi: 10.1177/039463200601900408. PMID: 17166400.

Dalton, K. and Holton, W.M. (1992), Diet of women with severe premenstrual syndrome and the effect of changing to a three-hourly starch diet. Stress Med., 8: 61-65. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2460080109

Dalton, K. and Holton, W.M. (1992), Diet of women with severe premenstrual syndrome and the effect of changing to a three-hourly starch diet. Stress Med., 8: 61-65. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2460080109

Margarita Raygada, Elizabeth Cho, Leena Hilakivi-Clarke, High Maternal Intake of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids During Pregnancy in Mice Alters Offsprings’ Aggressive Behavior, Immobility in the Swim Test, Locomotor Activity and Brain Protein Kinase C Activity 23, The Journal of Nutrition, Volume 128, Issue 12, 1998, Pages 2505-2511, ISSN 0022-3166, https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/128.12.2505.

Lv X, Xia Y, Finel M, Wu J, Ge G, Yang L. Recent progress and challenges in screening and characterization of UGT1A1 inhibitors. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2019 Mar;9(2):258-278. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.09.005. Epub 2018 Sep 14. PMID: 30972276; PMCID: PMC6437557.

He Jing , Zhang Hui-Ping, Research progress on the anti-tumor effect of Naringin, Frontiers in Pharmacology, Volume 14, 2023, DOI:10.3389/fphar.2023.1217001

CAMPANA, W.M.. (1995). Handbook of Milk Composition || Hormones and Growth Factors in Bovine Milk. , (), 476–494. doi:10.1016/b978-012384430-9/50022-6

Susan Thys-Jacobs; Paul Starkey; Debra Bernstein; Jason Tian. (1998). Calcium carbonate and the premenstrual syndrome: Effects on premenstrual and menstrual symptoms. , 179(2), 444–452. doi:10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70377-1

Thank for this informative article Kaya. I read the Dutch gynecology guideline on PMS and they are adamant that there is no place for progesterone in the treatment of PMS (based on the Cochrane review, ignoring all of Katharina Dalton's work). The recommended therapy for PMS is cognitive behavioral therapy. And if medications are used it is either inhibition of ovulation (with progestogen or worse) or an antidepressant. The guideline states that there are no hormonal differences between women, with the exception of serotonin. Serotonin is lower in women with PMS - so hence the recommendation to prescribe SSRIs. What do you think of the PMS - serotonin connection?

Isnt sweet potato also a good choice for luteal phase support?