How to Not Get Fat on the "Pro-Metabolic Diet"

A guide for switching to nourishing foods while avoiding fat gain

Disclaimer: This content is not intended as treatment or support for any medical condition. Content for entertainment purposes only. Not medical or health advice.

One day, on social media or elsewhere, you come across health accounts promoting a diet that’s all about increasing the metabolism. The diet is aptly called “the pro-metabolic diet.” You learn that sugar is good for us, that ice cream is a health food, that animal foods and rich meaty broths are healing, and that dairy is a superfood. You are promised that eating these foods will give you the same energy that you had as a teenager and that you will be lean, energetic and free of symptoms like brain fog, persistent fatigue, cold intolerance or PMS. You start eating this way but instead of feeling and looking better…you get fat.

What happened? Are these foods not pro-metabolic? Are they unhealthy? I’d say the foods themselves are fine…but there is a lot more to increasing the metabolic rate (and eating in a “metabolism-boosting” way) than just choosing to eat certain foods.

Eating your way to a higher metabolism can’t be summarized in a simple list of “good” vs. “bad” foods. What you need to succeed is to:

Know how to assess your biofeedback to see which foods work for you

Develop better habits around food and be consistent with meal times

Know how many calories you need to eat when starting out

Spot and correct gaps in your vitamin and mineral needs

Know how to pair foods to create balanced meals

Find a macronutrient balance that works for you

Know how to go about introducing new foods

The above skills will largely dictate whether the foods you eat help you feel healthier, get leaner, and increase your metabolism, or whether the “pro-metabolic diet” will turn into an anti-metabolic recipe for rapid weight gain.

This article will teach you how to do all this.

Additionally, at the end of this article, paid subscribers can access additional helpful resources, including:

Meal plans for different calorie levels (containing easy recipes)

A video guide on how to use Cronometer

A guide for tracking biofeedback

A Q&A for any additional questions that I will cover in a supplemental podcast episode

There’s More to Increasing the Metabolic Rate than Just Eating Certain Foods

There are many ways to go about increasing the metabolic rate. The focus of this article will stay on food. Other approaches for increasing the metabolic rate (such as hormone supplementation, light environment, and lifestyle habits) will not be covered here.

That being said, a general understanding of what “the metabolism” is and how there is far more involved in increasing it than just eating the “right” foods is important to grasp as a jumping off point.

About this time last year, I wrote an article titled “Eating a ‘Pro-Metabolic Diet’ Will Not Heal You.” In it, I covered the phenomenon of Dr. Ray Peat’s ideas about the importance of maintaining a high metabolic rate for optimal health becoming distilled into general dietary principles called the “pro-metabolic” diet on social media.

For those not familiar with Dr. Ray Peat, he was a biochemist and physiologist, with much of his work covering reproductive hormones, metabolism and nutrition.

The “pro-metabolic” diet has little to do with Dr. Ray Peat and is rather a way of eating that various online health enthusiasts came up with based on their interpretations of Dr. Ray Peat’s work.

The “pro-metabolic” dietary principles that you will find on social media aren’t bad per se. They focus on recommending nourishing foods and minimizing hard-to-digest or otherwise “anti-metabolic” foods (foods rich in compounds that mess with our cells’ ability to turn the foods that we eat into usable energy).

That being said, as I already spoke about in the above-mentioned article, increasing the metabolic rate is a multifaceted ordeal. The “eat this, don’t eat that” recommendations on social media do not encompass Dr. Peat’s writing, which focused on illustrating how various hormones, light, movement, nutrients (vitamins, minerals, macronutrients and types of fats), breathing patterns, thoughts and emotions, our social lives, professional fulfillment, environmental toxins, and all the other aspects of life can affect our cells’ ability to make the very energy that they need to sustain themselves, function, and let our body regenerate as opposed to degenerate over time. In other words, how all these factors affect the metabolic rate.

From Dr. Peat’s “about me” section on his website:

“I have a Ph.D. in Biology from the University of Oregon, with specialization in physiology. […] I started my work with progesterone and related hormones in 1968. In […] my dissertation (University of Oregon, 1972), I outlined my ideas regarding progesterone, and the hormones closely related to it, as protectors of the body's structure and energy against the harmful effects of estrogen, radiation, stress, and lack of oxygen.

The key idea was that energy and structure are interdependent, at every level.

Since then, I have been working on both practical and theoretical aspects of this view […] and therapeutic effects of the various life-supporting substances--pregnenolone, progesterone, thyroid hormone, and coconut oil in particular.

[…] It seems that all of the problems of development and degeneration can be alleviated by the appropriate use of the energy-protective materials.”

Instead of trying to explain Dr. Peat’s work to you, I’d encourage you to go straight to the source and read the articles on his website. You can also check out this repository where many have collected dozens of additional Dr. Ray Peat articles, interviews and newsletters created over more than 5 decades, many of which have not been published on his website.

Granted, considering the size of Dr. Peat’s body of work, and the fact that it focuses mostly on explaining biochemistry (and sometimes biophysics) as opposed to providing clear “do this, don’t do that” recommendations, I get that perusing his body of work isn’t everyone’s cup of tea. If someone is sick of being sick and just wants clear instructions for increasing their metabolic rate (ones that minimize room for error), getting that info by reading Dr. Peat’s works can be very time-consuming and not exactly straightforward. Not everyone is ready for that, not everyone wants to go through years of trial and error (obviously), and not everyone wants to become a hobby biochemist just to fix their health. I totally get that.

That being said, sometimes simple can become too simple. A list of foods to eat, promising that doing so will increase the metabolic rate, is too simple. Choosing the right foods is important, but it’s not all.

Foregoing all the other pillars of metabolism, if we keep the focus on food alone, how you eat is just as important, if not more important, than what you eat.

This article will focus on how to eat, as opposed to just what to eat, to make your diet metabolically supportive.

What Does It Mean to Have a High Metabolism?

Many people think of the metabolism as something that you’re born with that’s either “fast” or “slow.” The general thinking goes like this: if it’s fast, you can eat anything you want and stay lean. If it’s slow, you gain fat easily.

The above is partially true, but your metabolism isn’t some mysterious thing that you’re born with that’s either fast or slow forever and you can’t do anything about it. Your daily decisions affect the speed of your metabolism, causing your metabolic rate to fluctuate, increasing or decreasing.

The metabolism is the sum of all the life-sustaining biochemical processes. These are divided into three main categories:

Energy creation

Removing cellular waste

Building and maintaining structure

These processes are influenced by hormones, vitamins, minerals, oxygen availability, macronutrient balance, and the presence or absence of cellular toxins, like heavy metals or bacterial end-products.

Once again - the speed of metabolism always changes and fluctuates, and our lifestyle choices can either speed it up or slow it down.

The hormone that controls the speed of all of these processes (that controls the metabolic rate) is the thyroid hormone. This is the hormone that helps us make energy from food.

The foods we eat aren’t energy. They carry energy potential but need to be turned into usable energy by our cells. The food you eat can:

End up being turned into usable cellular energy (that your body will use for all of its functions, like keeping your organs functioning, supporting reproductive health, growing hair, thinking, repairing damage, and so on) and help build the tissues that make up your body.

End up being offloaded as heat.

End up being stored as body fat as opposed to being used for energy.

Whether you turn the food you eat into energy, store it as fat, or lose it as heat is controlled by your metabolism.

When the foods we eat (carbs, fats, proteins) are turned into energy, the cells that make up our organs and various systems in the body, like the hormonal, immune and digestive systems, can use this energy to maintain their function, structure and repair.

This is reflected by good health, absence of fatigue, ample energy, good sleep, sound digestion, good mood, rapid hair growth and skin repair, a strong immune system and an easy time staying lean. Many kids, teenagers and young people have these traits because they tend to have high metabolic rates.

If cells lack the needed cofactors for turning food into energy (these include thyroid hormones, vitamins and minerals, and oxygen), this energy potential ends up stored “for later” (it turns into body fat). This manifests as putting on fat easily, fatigue, poor sleep, poor digestion, hormonal issues, and aesthetic issues (like hair loss or skin problems). This is what you would call a “slow metabolism.”

You Can Be Lean and Have a Low Metabolism

“If I’m lean does that mean that my metabolic rate is high?” - Maybe. Or maybe not.

It’s possible to be lean while in poor metabolic health. This is why:

Since a slow or impaired metabolism is a state in which a person struggles to create energy from foods, build and maintain tissues, and remove waste, it becomes clear that thin people can also have a slow or impaired metabolism. Such people are usually experiencing a state of energy wasting and catabolism (tissue breakdown).

Sometimes, due to excessive oxidative stress, they might offload the energy potential of food as heat, without managing to turn it into enough usable energy for their cells.

These people are usually lean but struggle to build muscles, are highly anxious or depressed, have poor digestion and hormonal health, experience sleep difficulties, might have kidney or liver problems, might be excessively nervous, struggle to focus, and may suffer from mast cell disorders. In a person like this, increasing their metabolism (helping them make energy from the calories they eat) can increase their body weight, helping them build muscles and get out of a state of tissue and food wasting.

The phenotype of being very lean but in extremely poor metabolic health is best illustrated in severe illness.

In the cases of diseases of energy-wasting, like advanced cancer, intestinal malabsorption disorders, or type 1 diabetes, the building blocks for energy creation, like fats, proteins, and sugars, are lost in sweat, bowel movements and urine as opposed to being turned into energy. People suffering from these disorders can be very lean despite having extremely low metabolic rates. They have immense difficulty in absorbing foods and turning them into cellular energy and often suffer from extreme fatigue.

What Makes a Diet Pro-Metabolic?

In short, a diet that is “pro-metabolic” tries to provide an abundance of factors that help the body make energy while limiting those that interfere with energy production. Because, guess what, just because something has calories doesn’t mean you’ll be able to derive energy from it.

All food consists of a mix of the three macronutrients: carbs (sugars), fats, and proteins (alcohol is another macronutrient, but I’m not counting that one). These macronutrients provide calories. But the process of turning carbs, fats, or proteins (in cases where the other two are in short supply) into energy consists of many steps, all of which are powered by specific vitamins and minerals.

For example, this graphic below, from a 2019 research paper1 about the contribution of vitamins and minerals to solving diseases of cellular energy shortage, shows some of the different vitamins and minerals needed for the mitochondria to turn carbs and fats into energy.

To turn carbs (whether from pasta, potatoes or white table sugar) into energy, you need: vitamin B1, vitamin B3, vitamin B7, vitamin B9 (indirectly, by helping the body make parts of mitochondria), vitamin B12, magnesium, iron, manganese, copper, phosphorous, CoQ10, K2 MK-4 and taurine. Vitamin E and selenium are involved indirectly, by acting as antioxidants, preventing damage to mitochondria.

To turn fats (whether from beef tallow or cheese) into energy, you need: vitamin B2, vitamin B3, vitamin B5, vitamin B7, vitamin B9 (indirectly, by helping the body make parts of mitochondria), vitamin C, magnesium, iron, CoQ10, K2-MK4, and carnitine (a type of amino acid only found in meat). Vitamin E and selenium are involved indirectly, by acting as antioxidants, preventing damage to mitochondria.

Without these nutrients, especially the B vitamins and magnesium, which are pivotal to energy production, you won’t be able to turn carbs or fats into energy. Instead, they’ll end up either as body fat, or you’ll offload them as heat, in which case you might remain lean but you’ll still be tired and riddled with health issues.

Even though this might seem like a lot of nutrients, it’s still not all that’s needed for energy production.

While the above is what’s used directly by mitochondrial enzymes involved in energy production, the rate and completeness of energy production, and the ability to absorb carbs, fats and proteins in the gut and to get them into cells, is controlled by various hormones, like thyroid hormones, insulin, sex hormones, and pituitary hormones.

To make and use thyroid hormones you need selenium, iodine, vitamin D, zinc, and just enough vitamin A and iron (too much vitamin A and iron can have the opposite effect on thyroid hormone function).

For the body to make and use insulin you need potassium, chromium, zinc, vanadium and vitamin K.

To power the gut lining and absorb macronutrients you need glucose, zinc and glutamine, an amino acid found in gelatinous meats.

To lower stress hormones that interfere with the metabolism, and to make pro-metabolic sex hormones, like progesterone and the androgens, you need calcium, sodium, potassium, magnesium, vitamin K2, retinol (animal form vitamin A), vitamin D, vitamin E, zinc, vitamin B6, vitamin B9, and vitamin B12.

No, you don’t need to go out and get all of these as supplements. Nutrient-dense foods should cover most if not all of these requirements, as long as the right foods are eaten.

Considering Foods in Context

The concept of a nutrient-dense diet is not unique. Most nutritional authorities agree that you should eat nutrient-dense food. So how is the “pro-metabolic” approach different from your general recommendations to “eat the rainbow”?

Well, as mentioned near the start, the diet is inspired by the work of Dr. Ray Peat, who was a biochemist and physiologist, and as a biochemist and physiologist he had a somewhat more holistic view of the body, also considering:

Which foods provide nutrients in their bioavailable forms (in forms that are easily absorbed and utilized by humans). For example, many people struggle to use plant-based vitamin A (from carrots or pumpkins), especially if they’re hypothyroid, B12 deficient, or have certain genetic mutations

How various sex hormones (like estrogen, testosterone, or progesterone), neurotransmitters (like histamine, serotonin, or dopamine), and “stress hormones” (like adrenaline, glucagon or cortisol) affect the body’s ability to create energy and structure

How different macronutrients (fats, proteins, carbs) affect the rate at which cells make energy, as well as how macronutrient balance affects hormones

How certain types of fats, proteins and carbs affect hormonal balance, digestion, and cell structures differently than other types of fats, proteins and carbs, making some more optimal than others

How bacterial toxins and by-products, either from the fermentation of foods that a person struggles to digest, from the over-consumption of bacteria-rich foods (like fermented vegetables, kombucha or types of yogurt), or from pathogenic bacterial overgrowths in the gut, can impair energy production by acting like mitochondrial toxins

What makes the “pro-metabolic” diet recommendations somewhat unique is that they take into account the above.

As a result, some foods that are “nutrient dense” on paper (such as raw kale) are recommended against, because upon considering the overall biochemistry of that food, its goitrogen content makes it a “net negative” on the body. (Goitrogens are compounds found in certain raw plants that interfere with the creation of thyroid hormones.)

By considering the overall biochemistry of foods and their larger effect on the body, the “pro-metabolic” approach focuses on:

Whether foods have a lot of nutrients that humans can absorb, as opposed to just having lots of nutrients in theory

How certain foods and food compounds affect energy production as a whole

How certain foods and food compounds affect hormonal and gut health

Pro-Metabolic & Anti-Metabolic Foods

Below you will find listed the most common foods that are generally considered “pro-metabolic,” “anti-metabolic,” or “maybe pro-metabolic” based on their overall effect on the human body.

The “anti-metabolic” foods list is a pretty strict list of “no” foods, as covered in Dr. Peat’s research, with properties that can make them harmful to the body’s biochemistry, especially in high amounts.

The “pro-metabolic” foods list is a list of foods that are:

Often recommended in the “pro-metabolic” social media sphere and have been mentioned in Dr. Peat’s writing

Foods that people often end up basing their diets on when introduced to this ideology

Tend to support the metabolism while causing few issues for most people

The “maybe pro-metabolic” foods are foods that are:

Rarely recommended in the “pro-metabolic” sphere

And, or:

Foods that, in my opinion, can be highly “pro-metabolic” for some but “anti-metabolic” for others. This will depend on the person, and how well they digest and respond to any one of these foods biofeedback-wise.

Anti-metabolic foods: liquid cooking oils (like canola oil, corn oil, cottonseed oil, flaxseed oil, grapeseed oil, hemp seed oil, peanut oil, rapeseed oil, rice bran oil, safflower oil, sesame oil, soybean oil, and sunflower oil), margarine, conventionally-raised fatty pork and fowl, conventional lard, conventional duck and chicken fat, fish oil, fatty fish, nuts in high amounts (other than macadamia and coconut), seeds in high amounts, nut/seed butters, raw cruciferous vegetables (raw cabbage, kale, cauliflower, broccoli, turnips, rapeseed, radicchio, Brussel sprouts, kohlrabi), undercooked beans and lentils, unripe fruit, processed meats with added nitrites, highly-processed foods with added gums, thickeners, preservatives, and artificial flavours (like frozen chicken nuggets, hotdogs, chips, conventional store-bought cookies, etc), conventional, ultra-processed wheat products (think Wonder Bread, hotdog buns, Kraft mac & cheese), unfermented soybean products (soy flour, soy milk), vegan “fake meats,” vegan “cheese,” plant based milks (other than coconut milk), brown rice, high amounts of spinach, artificial and zero-calorie sweeteners (aspartame, acesulfame, stevia, etc), plant-based protein powders, conventional corn, extremely high-iron foods (like blood and blood-derived products), iron-fortified foods (like iron-fortified breakfast cereals).

Pro-metabolic foods: Ripe fruit (other than bananas), coconut oil, butter, ghee, tallow, cocoa butter, honey, sugar (white, brown, panela), maple syrup, molasses, gelatinous meats (like oxtail, chicken feet, shanks, tripe, cheeks), gelatin, collagen, colostrum, additive-free milk (especially A2 milk, from goats, sheep, buffalo, and Jersey and Guernsey cows), cheeses made with animal rennet (like Manchego or Parmigiano Reggiano), casein protein powder, potatoes, shellfish (like scallops, oysters, shrimp, etc.), lean white fish (like cod), fresh fruit juice, coconut water, pasture-raised eggs, organ meats, certain culinary fruits (zucchinis, bell peppers), raw carrots, ginger, sodas with minimal additives, coffee, organic nixtamalized corn, marmalades, ice cream, Brewer’s yeast (in supplemental quantities), mushrooms.

Maybe pro-metabolic foods: Sourdough bread, oats, traditional wheat variety pasta (like spelt), white rice, soaked and well-cooked beans and lentils, extra virgin olive oil, pumpkins and squashes, tomatoes and tomato sauce, eggplants, ripe bananas, plantains, salad greens (lettuce varieties, arugula), fermented foods in small amounts (sauerkraut, yogurt, kimchi, kefir, etc.), sweet potatoes, yams, other tuberous vegetables (beets, parsnips, celeriac, etc.), other vegetables (fennel, celery, etc.), spice blends, conventional cow’s milk, fermented soy products as seasoning (soy sauce, tamari, natto), resistant starches in small amounts (for example, potato salad), avocados, chocolate, culinary herbs, onions, garlic, muscle meats (chicken breast, turkey breast, steak), tea, dried fruit, pasture-raised pork and fowl, game meat.

If you want a deep dive into why certain foods (like vegetable/seed oils, fish oil, resistant starches, fermented foods, or foods excessively high in iron) are generally considered “anti-metabolic,” check out my other articles where I go into this in more detail.

Why Should You Avoid Fat Gain?

Excess body fat, generally defined as having a body fat percentage over 32-35% for women, and over 25-28% for men, can be anti-metabolic, contributing to:

Impaired glucose handling (by releasing free fatty acids into the blood, which compete with glucose for utilization).

High estrogen levels (as fat cells are where most of the estrogen synthase enzyme is expressed).

Interference with proper organ function (for example, interfering with the function of the liver and pancreas, fatty liver disease).

Inflammation and oxidative stress (since excessive body fat can produce inflammatory cytokines).

Most of these effects are greater in those who have a lot of visceral fat, which can be thought of as the “invisible fat” that’s stored inside the body, around our organs.

The visible fat, which is usually what we think of when we think of body fat, the body fat that makes us more “plump,” is called subcutaneous fat.

Some obese individuals can still be insulin sensitive, experience little inflammation, and have few issues burning glucose despite their high levels of body fat if they have lots of subcutaneous fat but little visceral fat.

On the other hand, some rather lean individuals can be “metabolically obese,” experiencing the above-mentioned negative effects, if a lot of their fat is visceral. Researchers call these people “metabolically obese, normal-weight” or MONW for short.2

A suboptimal metabolic and hormonal environment, such as the “chronic stress” hormonal environment present in those with low metabolic function, predisposes a person to gain more visceral fat. If a person increases food intake too rapidly when in that state, and especially if certain nutrient deficiencies haven’t been addressed or if the meals are imbalanced, a person might gain quite a bit of visceral fat.

Although subcutaneous fat is not as directly involved in interfering with energy metabolism as visceral fat, subcutaneous fat, especially subcutaneous belly fat, can lead to greater increases in estrogen than visceral fat.3 This can contribute to metabolic impairments more indirectly, while also leading to a worsening of PMS, anxiety, autoimmunity and MCAS.

In short, if the process of trying to fix your metabolism leads to lots of fat gain, it becomes a case of one step forward, two steps back.

How To Avoid Fat Gain On a Pro-Metabolic Diet

Don’t Rapidly Increase Your Calories

The more your metabolic rate increases, the more calories you can eat without experiencing fat gain, as your body becomes better adapted to turning foods into energy as opposed to storing them as fat. “More calories in, more calories out.” Sort of like a teenager who can eat almost anything and stay lean.

However, this does not happen overnight. If your body is used to running on, let’s say, 1,500 calories per day, and you then, overnight, start giving it 3,000 calories per day, it’s unlikely that your metabolic rate will instantaneously adjust to running on 3,000 calories per day.

If you go from eating mostly plant-based, or if you are used to skipping meals and fasting, or if your previous diet consisted of mostly ramen noodles and toast with jam, or zero-calorie sweeteners in place of sugar, you probably ate a very low-calorie diet overall. When we eat in a caloric deficit for a long time, the body will lower the metabolic rate to stop us from wasting away.

If you then start eating consistent meals throughout the day, and these meals consist of ripe fruit, coffee with sugar, oxtail with potatoes, cheese with jam, and full-fat milk, you are most likely astronomically increasing your calories while eating the same volume of food.

I think the biggest misconception that I see among many who start eating in a more “pro-metabolic” way is thinking that you can eat as many of the “pro-metabolic foods” as you want without them causing fat gain just because they’re “pro-metabolic.” The main reason why people gain fat on the pro-metabolic diet is that they don’t realize how calorically dense many of the foods on the “pro-metabolic foods” list are, so they rapidly increase their calories when making changes to their way of eating.

A bowl of ramen noodles from a packet and a bowl of oxtail soup with potatoes might fill you up and make you feel satiated the same way, except the former might be 200 calories while the latter is closer to 800.

Of course, the latter meal is more nutritious and has more of the vitamins and minerals that the body needs to make energy from the calories you eat, but the body’s metabolism needs some time to adjust.

Get an Idea of Your Starting Calories and Macronutrient Balance

Before you consider rapidly overhauling your eating habits, use the app Cronometer to measure your current food intake first.

That is, before you make any changes to how you’re eating, take some time to track your current eating habits. That way you’ll get a better idea of your starting calories and your current macronutrient balance (how many grams of carbs, fats and protein you’re eating per day on average), which is also extremely important.

To do this, you will also need a kitchen scale that you can use to measure all the ingredients that go into your meals.

Yes, tracking and weighing your food is a hassle, I know. But doing so minimizes the margin of error and can really help you succeed. Plus, after about a week of doing so, it becomes sort of a habit and almost second nature.

I would track your current food intake for at least one week. That way you can also see if:

Your macronutrient balance is consistent (for example, do you eat mostly fat and barely any carbs on some days, or mostly carbs on other days)

Your caloric intake is consistent (do you eat 1,000 calories some days but 2,000 on other days?)

Your diet is missing any key nutrients needed for energy metabolism (In Cronometer, you can see whether your current diet meets the theoretical vitamin and mineral RDAs. If, for example, your data shows that you’re always under-consuming vitamin B1 and magnesium, you might be deficient in these important metabolic cofactors, predisposing you to gaining fat when eating carbs. If your diet is consistently low in B2 and B5, you’ll be more likely to gain fat from dietary fats.)

Once you know how many calories you’re eating, get an idea of how many calories you should be eating. To track this, use the Basal Metabolic Rate calculator, where you put in your: height, weight, gender, and current activity level.

Suppose the estimate given is a lot higher than what you’re currently eating (for example, you’re currently eating 1,200 calories a day to maintain your weight, but the calculator says that you should be maintaining your weight on 2,000 calories with your current activity level). In that case, you will have to increase your calories slowly, through a process called the “reverse diet.” How to do this is covered in the “Use the ‘Reverse Diet’ Method” section of this article.

Ideally, over time, you should be able to eat more than even the BMR estimate. In older literature from 50-100 years ago, from a time before metabolic suppression was as much of an epidemic as it is today, women, even when generally sedentary, were estimated to eat between 2,500 to 3,000 calories per day, and men 3,000 to 3,500 calories per day, while remaining lean.

However, getting from a point where you need to eat only 1,200 calories to maintain your weight to a point where you can maintain your weight on 2,500 calories will take time, perhaps even 1-2 years.

Don’t Overeat on Non-Satiating Foods

Under the point of calories, it is worth mentioning that it is easier to overeat when basing your diet on a lot of calorie-dense but not satiating foods, especially when starting from a place of years of severe caloric restriction. These are foods like ice cream, marmalades, cheese, dried fruit (like dates), “liquid calories” (like orange juice and whole-fat milk), and sugar (or honey, maple syrup, etc.) added to foods and beverages.

When you start introducing more “pro-metabolic” foods, prioritize ripe fruit (for example, papayas, mangoes, melons, oranges, cherimoyas, clementines, pears, apples, and peaches) over fruit juice. Treat ice cream as a treat. Eat more solid foods instead of liquids. If you start adding sugar to your beverages, start with one teaspoon, and work up from there over a few weeks.

More satiating solid-food options can be whole fruits, cooked/baked fruits (like cooked pears or baked apples), potatoes, yams (if tolerated), nixtamalized corn tortillas, a stew made with leaner gelatinous meats (oxtail from the lower part of the tail, beef knuckle, skinless chicken drumsticks, beek cheeks, tripe, tendons), shellfish (shrimp, mussels, scallops, crab, octopus, squid), white, lean fish (like cod or haddock), reduced-fat cottage cheese or quark, Skyr, aspic, and, if tolerated, dishes containing lots of culinary fruit, like zucchinis, bell peppers, eggplants, tomatoes, pumpkins and squashes.

These foods increase meal volume (the meal feels bigger in your stomach), so it’s harder to over-eat on them.

“Pro-Metabolic” Foods Tend to Be More Calorically Bioavailable

Although I am pretty sure that the term “bioavailable calorie” is something that I just made up, let me explain what I mean by it.

Someone might start tracking their food intake and realize that on their current diet, they are eating 1,800 calories per day. They make a switch to eating more “pro-metabolic” foods, still eating 1,800 calories per day but…now they’re gaining fat. What happened?

A few things can be happening here. Maybe the person increased their carb intake by a lot (changed their macronutrient balance rapidly), while deficient in the vitamins and minerals needed for carb burning.

Maybe some of the foods they introduced (like dairy or certain fruits) don’t work for their gut or are causing a mild allergy and increasing inflammation, which can impair energy production. These issues can be remedied by making changes slowly and paying attention to biofeedback, which will be discussed shortly.

However, another explanation can be that, by eating more easily absorbable foods, a person absorbs more of the calories they’re eating now, even though the calories on paper stay the same.

Dietary fibre can sometimes act like an “antinutrient,” trapping carbs and fats in the digestive tract and preventing their absorption.

Suppose someone was eating 1,800 calories on a high-fibre diet (full of vegetables, whole grains, beans, and high-fibre fruits like berries and apples). In that case, it’s likely that a decent portion of the fat and carbs they consumed in the meal got trapped by the fibre and moved out of the body in a bowel movement, instead of being absorbed.

Many of the foods recommended on the “pro-metabolic foods” list are lower in fibre and easily digestible. This is a feature, not a bug. For many sick people, who have an overgrown and dysbiotic gut microbiome from years of metabolic suppression, fibres that linger in the gut too long can feed gut pathogens (expecially when dealing with bacterial translocation), contributing to making the gut more “leaky,” and allowing harmful substances (like bacterial endotoxin) to escape the gut. This in turn increases inflammation and can directly lead to impairments in energy production.

However, rapidly switching to an isocaloric (equal in calories) but easily digestible diet can increase the calories absorbed. In other words, even though, on a “pro-metabolic diet,” a person might be eating the same calories on “paper” as before, they likely absorb more calories.

Because the digestibility of foods can affect how we react to dietary changes, the second step, “Make Changes Gradually,” is so important.

Make Changes Gradually

Any time you make major dietary changes, you won’t know how your body will respond. Making drastic changes right off the bat and flipping your eating habits on their head can feel motivating in and of itself because it feels nice to achieve something. Sometimes it can even provide a newfound sense of identity (think of that one friend who went vegan or keto and suddenly that’s all they talk about). However, with too many changes all at once, if problems arise, you won’t know what’s causing them.

Step 1: Remove Anti-Metabolic Foods

I would probably start by simply omitting foods from the “anti-metabolic foods” list. That is, I would keep your current eating habits (whatever they are) the same, calories and all, only switching to avoiding any of the foods from the “anti-metabolic foods” list.

You can also make some “switches” to the foods from the “maybe pro-metabolic” foods list (for example, if you eat wonderbread daily, try replacing it with sourdough, or replace raw kale with well-cooked kale).

I would do this for one week before making additional changes, to see how your body adapts.

Step 2: Adjust Meal Frequency

Keeping with the theme of making changes one at a time, I would then make changes to your meal frequency (how you eat).

While adjusting meal frequency, you are still keeping your old calories and your general food choices the same (with the only change being avoiding “anti-metabolic foods”).

For example, if you’ve never been a breakfast person, try having breakfast consistently first thing in the morning (while keeping your overall daily caloric intake the same.) If you’re struggling with not being hungry in the morning (a sign of high nighttime stress and metabolic suppression) start with something small: a piece of fruit or a small glass of juice. If you don’t like traditional “breakfast foods,” try eating some dinner leftovers.

If you’re a coffee drinker, now is also the time to start having coffee only when in the “fed” state. Have coffee with or after a meal, as opposed to on an empty stomach.

Alternatively, if you already eat breakfast but are known to skip meals (for example, only having one big meal in the morning and another before bed) try switching to having smaller meals more frequently (starting with having breakfast, lunch and dinner daily, later adding in snacks if your hunger demands so). Again, make sure to stay within your current baseline calories. Do this for at least two weeks while tracking biofeedback.

Step 3: Increase Your Calcium Intake

Low dietary calcium intake (as is common on many currently-trending diets, like keto, vegan or paleo), is indirectly anti-metabolic. It increases hormones like PTH, prolactin and cortisol, which are used to pull calcium from your bones and get it into the blood to keep the nervous system running. This is destructive to the body (obviously, you’re breaking yourself down) and can paradoxically contribute to tissue calcification. Most importantly, these “stress hormones” also interfere with energy production and can cause an unfavourable imbalance in the sex hormones. Plus, the body tends to “hide” toxic metals (like lead or cadmium) in bones, so by constantly dissolving your bones on a low calcium diet, you can release these metals into the blood. From there they can relocate to more delicate tissues, like the brain, where they have a much greater potential for causing damage.

In short, low-calcium diets are anti-metabolic and stress-inducing, and simply increasing calcium intake can prevent these effects.

Due to calcium’s anti-stress effect on the body, research finds that high-calcium diets lead to more fat loss and help prevent fat gain.4

Dairy is the best calcium source, as the calcium in it is highly bioavailable (easy for the body to absorb).5 Dairy fat also naturally contains vitamin K2, which is needed to help the body get calcium into the right places.

If you’ve cut dairy out of your diet and have been only drinking plant “milks,” try slowly replacing them with dairy (again, while keeping overall calories the same).

You might have to start with one teaspoon of milk on “day 1.” Increase that to 3 teaspoons on “day 2,” until your gut can tolerate a full glass of milk. The slow introduction helps avoid digestive problems. If you cut out dairy, the gut stops making enzymes needed to digest it and might need some time to readjust and start making them again.

Once you get to a point where you can tolerate dairy again, use Cronometer to ensure that you’re getting at least 1 gram of dietary calcium daily (ideally closer to 1.5 grams).

If cow’s milk negatively affects your biofeedback, making you feel worse or more inflamed, try goat milk instead. If you can’t tolerate milk, try aged cheese (such as Parmigiano Reggiano, Pecorino Romano, or Manchego) which tends to be easier to digest. If no dairy works for you right now, then this change isn’t right for your body (right now).

Switch to coconut milk instead and use eggshell powder or oyster powder as a calcium source. If using a calcium supplement (like eggshell calcium), take it with a food source of vitamin K (like dark chicken meat, liver, or leafy greens). Nixtamalized corn tortillas are another good calcium source (they have to be nixtamalized, as that’s what increases their calcium content).

If dairy is already part of your diet, try to have more dairy in places of other protein sources. What works for me is usually only having meat with one meal per day (lunch or dinner) and having dairy (in the forms of skim milk, cheese and Skyr yogurt) as the main protein at my other meals.

The most important point here is to get a minimum of 1 - 1.5 grams of dietary calcium daily (ideally not exceeding 2.5 grams for most people).

Step 4: Introduce More “Pro-Metabolic Foods”

At this point, I would gradually start making more changes to what you eat.

For example, if you’ve only ever eaten muscle meats (chicken breast, steak), try switching those out for more gelatinous meats (aspic, beef cheeks, oxtail stew, tripe etc.). Do this for a few days and see how you feel. If your biofeedback is better, then this change works for you.

If you mainly eat noodles or bread for carbs, try replacing these with fruit and potatoes. Once again, do this for a few days and see how you feel.

Select a week to try to eat more shellfish and organ meats (like liver, heart or gizzards) in place of lean meats. See how you feel that week.

Start using coconut oil as your main cooking fat.

If you consume a lot of raw vegetables, see if you feel better if you eat more of your vegetables cooked or baked, as opposed to raw, for one week.

Once again, make changes slowly and gradually. If you’re introducing foods that you’ve never eaten before into your diet, introduce one new food per day or once every few days. That way, if you react to any new food, you can catch which one it is.

Going slow is important because eating foods that cause digestive distress or activate the immune system (cause us inflammation) is the opposite of “pro-metabolic,” and can contribute to fat gain. Since we are all slightly different, diverse reactions to foods from one person to another are expected. The goal is to help you spot what works for your unique build.

Step 5: Spot and Remove Problem Foods

Many of the foods from the “maybe pro-metabolic” foods list are my daily staples. Vegetables, especially onions and garlic, can make a meal far more interesting. Oats are a warming and satiating way to start the day. Chicken breast can be a great protein for a rice curry.

I don’t think it’s necessary to only sustain yourself on the foods from the “pro-metabolic list.” What is important though is to:

Avoid/limit foods that cause digestive distress (bloating, gas, runny stools, constipation)

Avoid foods that contribute to inflammation (water retention, swelling, brain fog, joint pain, inability to warm up after a meal)

Try to eat more gelatinous meats/gelatin relative to muscle meats

If you notice that certain specific foods cause these problems, it’s best to cut them out. As mentioned already, eating foods that cause digestive distress or activate the immune system (cause us inflammation) is the opposite of “pro-metabolic,” and can contribute to fat gain.

Many people are sensitive to grains, even if not Celiac, without realizing it, as there are no reliable tests for food sensitivities. To see if this is you, try cutting out all grains (this includes rice, corn, oats, bread, pasta, etc.) for 30 days to see if you feel any better. If you see no improvements, then congratulations, you’re not grain-sensitive, feel free to bring these foods back into your diet!

Try playing around with your fibre intake too. See if your biofeedback (digestion, mood, energy) is better with more vs. less fibre. Some very sick people can only tolerate very few fibre sources until their digestion improves. Raw carrots are a fibre source that works well for most. For some, raw carrots might be the only tolerable fibre source for some time. The most important thing is, once again, to see what works for you and your biofeedback.

Generally, the more the metabolic rate improves, our tolerance for a wide array of foods and the ability to digest them improves. Reacting to various fibres (from vegetables, legumes or fruit) can be a sign of bacterial overgrowths in the gut, slow digestion, or a dysbiotic gut. Reacting to “immunogenic” foods like gluten and dairy usually signals a disrupted gut barrier and high estrogen and prolactin. Including lots of gelatinous meats/gelatin in the diet should be helpful in overcoming this problem over time.

Thankfully, these states improve as the metabolic rate increases, helping us get to a point where we can tolerate and eat a wider array of foods.

Still, you need to meet your body where it’s at.

Use the “Reverse Diet” Method

A “reverse diet” is the process of slowly increasing your caloric intake over time to help increase the metabolic rate.

As you make the above changes, you might notice that your metabolism is a bit faster already. You might notice that you’re losing some fat, or are way hungrier than usual. This makes sense, as you’ve removed some of the metabolism-inhibiting dietary substances and are starting to eat more mineral and vitamin-rich foods.

These signs, especially if accompanied by improved biofeedback, mean that your metabolic rate is speeding up and that you need to start increasing your calories.

For anyone eating below their current optimal calories as per the BMR calculator, and especially if already lean, increasing your calories as your metabolism increases is an absolute must. Otherwise, you’re just placing the body under more stress, telling it to ramp up all of its processes and use up nutrients at a faster rate, without giving it the needed fuel and nutrients to do so without wasting away and worsening vitamin and mineral deficiencies.

Now, to do a reverse diet, increase your calories very slowly. I would increase your total calories by 50 calories every two weeks. For example:

If you started at 1,800 calories, increase them to 1,850 for two weeks. After two weeks, increase them to 1,900. After another two weeks, increase them to 1,950.

Ideally, you should continue this process until you hit the calorie goal calculated by the BMR calculator. After hitting that goal, continue increasing your calories by 50 every two weeks if your biofeedback (hunger, energy, weight, sleep quality) tells you that you need more food.

Do all of this while tracking your biofeedback. This includes tracking any potential fat gain. For example, if after two weeks on 2,100 calories, you notice that your hip/waist/thigh measurements increased, lower your calories back to 2,050 and stay at those calories for another two weeks, before retrying increasing your calories to 2,100 again.

As you’ll see in the attached meal plans, increasing calories doesn’t have to mean eating an additional meal or eating vastly different foods. You just slightly tweak the ingredient amounts. It can be as simple as making your morning oats with 50 grams of oats and 10 grams of coconut oil, as opposed to 40 grams of oats and 8 grams of coconut oil.

Ideally, most of the additional calories should come from carbohydrates, then protein and then fats (in that order). This will be discussed more in the next section - “Don’t Eat High Carb and High Fat.”

Don’t Eat High Carb and High Fat

If there is one takeaway that you get from this article, I want it to be this: a diet high in both carbs AND fat is a recipe for rapid fat gain.

First, to set some context in place, here are two widely popular ideas about fat loss (and generally how the body works) that are totally wrong:

Your body has a magical “fat burning” vs. “carb burning” switch on its dashboard that you have to flick in either direction, making your body rely entirely on either carbs or fats for energy.

You need to burn fat to lose fat, and you can’t lose fat when eating carbs.

To the first point, the body is made up of trillions of cells, and while any cell can only burn one fuel source (either carbs or fat) at any given time, your body is always using both carbs and fats for energy, based on different cells’ preferences at any given time. In other words, at any given time, some of your cells are burning fat while others are burning glucose.

To the second point, when isocaloric (equal calorie) high-fat, low-cab and low-fat, high-carb diets were compared for fat loss, those on the low-fat, high-carb diets experienced more fat loss.6

This is because:

Different ratios of the macronutrients (fats, carbs and protein) in the diet differently affect our hormones (like insulin, thyroid hormones, cortisol and sex hormones). Higher carbohydrate intake increases the levels of “pro-metabolic” hormones like thyroid hormone, progesterone and testosterone. High-carb, low-fat diets also make us more insulin-sensitive, by lowering cortisol, a hormone that drives insulin resistance.

Glucose and fat compete at the level of each cell to be the chosen fuel for burning. Reducing fat intake on a low-fat, high-carb diet makes it easier for glucose, our cells’ preferred fuel, to be burned for energy. This can help remedy high blood sugar levels.

Both high-fat, low-carb and low-fat, high-carb diets tend to be effective strategies for losing fat and preventing fat gain. The difference is how they affect hormonal health.

Low-carbohydrate, high-fat diets tend to “hide” the issue of damaged sugar metabolism (by drastically cutting carbs) and temporarily relieve symptoms. Sadly, long-term they tend to wreak havoc on hormonal health, lowering thyroid hormone levels, lowering the levels of progesterone and testosterone, and making us more insulin resistant.

On the other hand, higher carbohydrate, lower fat diets, as mentioned earlier, increase thyroid function and promote insulin sensitivity, improving the body’s ability to use sugar for energy and manage blood sugar levels.

This is something that I wrote about in much more depth in this article.

“Wait, I Thought We Should Combine Fats, Carbs and Proteins at Each Meal for Balanced Blood Sugar”?

Reading above about how reducing fat intake can help you be a better sugar burner, remedy insulin resistance and help you achieve better blood sugar balance long term might have you going - “Wait, I thought we need to combine carbs, fats and proteins at each meal to balance blood sugar?”

Here’s the thing though - the types of carbs you eat will define just how much you need to worry about having to pair them with fats and proteins.

Fat and protein can slow down the digestion of starchy carbs. Starchy carbohydrates (like rice, oats, potatoes, or bread) consist of pure glucose. Pure glucose, if eaten on its own, rapidly enters the bloodstream (it has a high glycemic index). Pairing these types of carbs with fats and protein helps to slow down glucose’s entry into the blood, creating a more stable blood sugar response.

If you are bad at burning sugar (for example, because you’ve been very low carb for a long time, are hypothyroid, or are vitamin and mineral deficient), then the rate at which your cells can burn glucose might be quite slow. In this state, if glucose from a meal enters your bloodstream quickly, it might “out-speed” the pace at which your cells can take it up. This shows up as high blood sugar and blood sugar spikes.

Your blood acts as a “fuel delivery highway,” and when your cells take up glucose, they remove some of it from the blood to burn it for energy. High blood glucose and “blood sugar spikes” are like cars piling up on the highway because the exits are blocked. Blood sugar spikes and chronically high blood sugar are stressful to the body and should be avoided.

Adding protein and fat to your starches helps to prevent this, slowing down the digestion of starches, making glucose enter the bloodstream more slowely and gradually.

However, at the cellular level, excess fat (especially excess long-chain saturated fatty acids, which take more time to burn) can block cells from taking up glucose by competing with it for being chosen as fuel. This in turn ends up “blocking off the highway exits” even more. (This is covered in more detail in this article).

Uniquely, fructose-containing carbs can help keep blood sugar more stable, even if eaten on their own. This is because fructose doesn’t immediately enter the bloodstream. It is first sent to the liver, where it helps to replenish the liver’s energy stores. The liver then converts it to glucose that it then gradually releases into the bloodstream. Fructose-rich carbs are the sweet-tasting carbohydrates, like fruit, honey, cane sugar and juice.

Prioritizing carbs that enter the bloodstream more gradually (like fruit) helps to keep blood sugar levels more stable when you drop your dietary fat intake. This makes fruit a good choice, especially for those who might struggle with effectively burning sugar for energy. As a general principle, Dr. Peat’s work was more in favour of fruit and “simple sugars” (like cane sugar) as opposed to starches, and this is part of the reason why.

If eating starches, always pair them with fat and protein to avoid rapid changes in blood sugar. Eating sweet carbohydrates is more forgiving. (Of course, in this sense the term “sweet carbohydrates” obviously doesn’t include things like cookies or cake, which are starch-containing. I’m talking fruit, dried fruit, cooked fruit, honey, plain sugar).

Getting most of your daily carbs from fruit and culinary fruit (like squashes or pumpkins) will let you get away with reducing fat intake more, without it causing blood sugar rollercoasters.

In other words, eating fruit on its own is going to be fine for most people. Eating rice on its own is a bad idea for most, and it would be a much more balanced meal if you added some butter and chicken to it.

A “Pro-Metabolic” High-Carb Diet Needs to Be Lower in Fat

A piece of wisdom that has very much been omitted in much of the social media disrourse around “pro-metabolic” eating is that high carb diets intended for improving the metabolic rate and inducing fat loss, as in line with both existing research and what has been said by Dr. Peat himself, need to be low in fat.

If the goal is to improve metabolic health, then any variant of the “pro-metabolic” diet should be designed in a way that makes it a high-carb, lower-fat diet. The whole point of going low fat and high carb is to help restore proper sugar metabolism, something that is faulty in all chronic illnesses of metabolic suppression.

The most common blunder that many make when switching over to eating more nourishing foods is unintentionally entering the “Macronutrient Swampland” (covered in the next section), eating both high fat and high carb.

It is possible (and advisable) to have carbs, fats and protein all together in a meal, but just how much of each you have in a meal will decide whether or not you dip into the “swamp.” This will be covered in more detail in the “Balance Your Macronutrients” section of this article.

Are You in the Swamp?

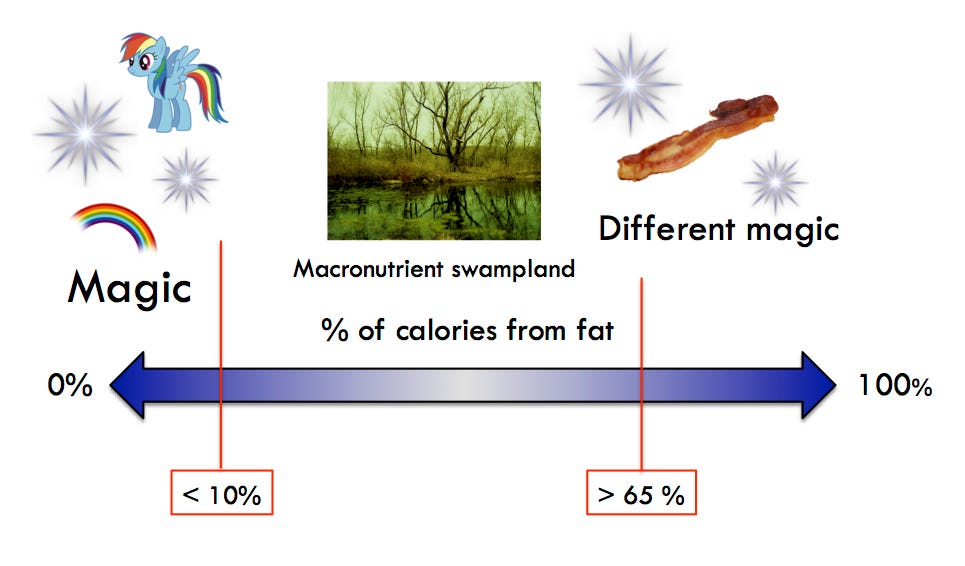

In her iconic article “In Defense of Low Fat,” writer Denise Minger coined the term: “Macronutrient Swampland.”

In Denise’s article, the “Macronutrient Swampland” is the zone where both dietary fat and dietary carbs are high. The Standard American Diet (SAD) is in the “swampland,” being about 35-45% fat, 40-50% carbs, and 15% protein. “Swampland” diets tend to worsen insulin resistance and increase fat gain by promoting over-eating.

Outside of the “swampland” are the areas where “magic” happens. These are diets that are either very low fat (under 10% of total calories as fat) or very low carb (keto diet, less than 10% of total calories as carbs).

The “magic” in question is either effortless fat loss, the reversal of disease symptoms (such as the disappearance of insulin resistance on very low-fat, high-carb diets, as noted in Denise’s article), or both.

What Makes “The Swamp” So Bad?

Being in the “swamp” can make it extremely easy to put on excess weight. Here is why:

Impaired glucose burning: If we have both lots of glucose and lots of fat in the blood, we are making it harder for glucose to enter cells (by promoting the competition between fats and carbs). If the body can’t burn fuel, it’ll store it as fat. A diet that’s too high in fat, stress (this includes psychological stress but also biological stress, like hypothyroidism) and being overweight are all factors that cause the liberation of excess fat into the blood and promote glucose-fatty acid competition.

Food palatability: Pairing carbs and fats together also makes foods a lot tastier, making it easier to overeat. If you try eating plain sugar out of the bag, it’s pretty bleh. If you try eating a stick of butter on its own, it’s sort of revolting. But if you mix sugar and butter to make caramel? Delicious.

Caloric density: Fats are more calorically dense than carbs or proteins. A gram of carbs is 4 calories. A gram of protein is 4 calories. A gram of fat is 9 calories. By using lots of butter or tallow in your cooking you can easily skyrocket your daily calories, since just a tablespoon of fat is 90 calories. This extra fat also makes it much easier for you to land right in the “swampland.”

Now, being in the “swamp” as far as weight maintenance goes might not be so bad if you’re eating in a caloric deficit (below your maintenance calories), or at maintenance.

The issue is that the “swamp” makes it so easy to over-eat, especially if you’re not tracking your food and just cooking intuitively.

A counterargument is sometimes “Well then how do we explain the French?” Many Frenchmen (and women) 100 or 200 years ago, eating the traditional French high-carb and high-saturated-fat diet, remained lean because they:

Have always eaten like that (no history of dieting or depressed metabolisms)

Ate at maintenance (their maintenance calories were high because they were in good metabolic health, so it was hard for them to reach what would have been a caloric surplus)

I believe that the people who maintain or lose weight while eating a “pro-metabolic” type diet that falls into the “swamp” macronutrient-wise do so because, fundamentally, they are eating at maintenance. Since the foods they’re eating are more nutritious, they have more resources to make energy and are able to handle more calories without gaining fat.

Not everyone adapts this way though, especially not if their hunger signals are damaged, if they’re coming from very low-calorie diets, or if their metabolism is damaged past the point where just eating real food can be enough to restore it.

Unfortunately, for someone coming from a background of under-eating and metabolic illness, who might be riddled with autoimmune diseases, has impaired sugar metabolism due to years of chronic stress, and has eaten 1,500 calories a day most of their adult life, a sudden mix of high carb + high fat + excess calories, often equals:

Staying outside of the “Macronutrient Swampland” and going slow with changes (as outlined in the “Make Changes Gradually” section) can help you avoid this.

In summary, one of the foundational goals of eating in a truly “pro-metabolic” way is to help restore proper sugar metabolism, which is done best on high-carb, low-fat diets. Anyone who is metabolically ill, overweight or stressed tends to excessively rely on fat burning and excessively release fat that’s stored in their body into the blood. Limiting dietary fat helps to get their cells to learn to burn glucose again, while an excess of dietary fat when in that sick state, interferes with this process.

How Do We Define “The Swamp”

In Denise Minger’s article, she classifies low-fat diets with 10% or less of total daily calories coming from fats as “outside the swamp.” This is based on the work of those like Walter Kempner (which I covered in this article) who cured hypertension, obesity and diabetes with diets of nearly 100% carbohydrate, and the diets of allegedly long-lived tribes, like the Okinawans or Bantu, whose diets were somewhere in the 10-15% of total calories from fat range.

I am a bit more forgiving in my estimates. In my world, anything under 30% of total calories as fat if you’re lean, and under 20% of total calories as fat if you are overweight, would be considered a low-fat diet.

Why the forgiveness? In my experience, for most people, a diet with less than 15% of total calories from fat creates new sets of issues, especially if a person is lean and insulin-sensitive. These issues include adrenaline surges, sleep troubles, vitamin deficiencies, and a tanking of the sex hormones. If a person is more overweight (meaning they already have more fat in the blood), they can usually get away with dropping their dietary fat lower.

Still, I think staying between 15% and 29% of all calories coming in from fats is optimal for most people.

For anyone who might be having a knee-jerk reaction to the idea of a lower-fat diet after surviving the 1990s, it is worth noting that, as mentioned in Denise’s article, even during the low-fat diet craze of the 1990s, most of the recommended diets weren’t really low fat. They recommended dietary fats to be kept at 30% of total daily calories, which is entering “swampland.” That time was also characterized by the popularization of margarine over butter, canola oil over coconut oil, and a general craze for whole grains and ultra-processed foods. Some of the good ideas from back then (such as the idea of reducing dietary fat to lose fat, something that bodybuilders know and do to this day) were muddied by plenty of other bad ideas, leaving a bad taste in many people’s mouths (literally and figuratively). Let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater though.

How to Escape the “Swampland”

1. Slow Transition

If you have been eating low-carb/high-fat for a long time, or if you notice that you gain fat very easily from carbs, the escape from the “swamp” will have to be done gradually. You will have to slowly increase your carb intake, while also replenishing key nutrients and gradually reducing your fat intake. For example, increasing your carb intake by 30 grams each week, while dropping your fat intake by 15 grams each week, to keep your baseline calories the same.

A general macro split to strive for eventually would be:

50-70% of total calories from carbs

15-29% of total calories from fats

15-21% of total calories from protein

2. Address Your Vitamin and Mineral Needs

I think that almost anyone who notices that carbs make them put on body fat (and by carbs I mean fruit, plain sugar, or honey, and not cakes or cookies, as the latter aren’t carbs but a mix of the 3 macronutrients, usually somewhere in the “swamp”), should consider supplementing with vitamin B1 (or a B complex with a bioavailable B1 source, like sublingual TPP), and magnesium, as these two micronutrients are vital in burning carbs for energy.

Deficiencies of other key nutrients (like copper, zinc, potassium, chromium, manganese, vitamin B3, or vitamin B7, to mention a few) can be some other bottlenecks for energy production and sugar metabolism. If you track your food intake in Cronometer and notice that, for a week straight, you never hit the theoretical RDA for a certain nutrient (like copper or vitamin B3), it might be safe to assume that you’re deficient in that nutrient. In that case, I’d make the effort to eat more foods containing that vitamin or mineral.

Long-term, improving thyroid function and replenishing key nutrients, will help you tolerate a lot more carbs, ideally getting to a point where, with time, 50-70% of your total daily calories are coming from carbs.

3. Stop Adding So Much Fat to Your Meals

Adding fat to your meals (like butter, tallow, or cheese) without tracking is a recipe for landing in the “swamp.” This is probably the main habit that lands many in the “swamp.”

Many of those coming from a more animal-based or “Weston A. Price Foundation" dietary background have the habit of using lots of fat in their cooking. Once this habit is combined with adding more carbs to meals, fat gain is imminent for many.

Since many nourishing foods (like eggs, cheese or oxtail) are already high in fat, eating them with added fat and plenty of carbs is an express ticket into the middle of the “swamp.”

For example, let’s say that you’re making a 2-egg omelette with fruit for breakfast.

If you mix 2 eggs with some high-protein Skyr yogurt, use a ceramic non-stick pan to fry them up, and have about 500 grams of fruit on the side, your meal will be at 22% fat, 61% carbs and 17% protein. As per my definition of the swamp, you are not in the swamp.

Now, let’s say that you still use your 2 eggs and protein yogurt, but also put a slice of cheese in your omelette and add 20 grams of butter to the pan. Now you are at 42% fat, 42% carbs, and 15% protein - deep in the trenches of the swamp.

You might notice that many social media recipe accounts that use lots of fat/fatty meats in their cooking have relatively little carbs on their plates. They are escaping the swamp in the opposite direction. However, a high-fat/low-carb diet is not “pro-metabolic,” even if the “right” “pro-metabolic” foods are being eaten. This is something that even some “pro-metabolic” content creators seem to be confused about.

4. Eat More Lower-Fat Proteins

Protein sources that are lower in fat and will help you stay out of the “swamp” if you make them the main proteins in your diet are:

Shellfish (shrimp, squid, clams, mussels)

Lean white fish (haddock, cod)

Skyr, fat-free quark, skim milk

Tendons, tripe, cartilage

95% lean ground beef

Skinless chicken

Gelatin/collagen

Beef cheeks

Proteins that are very fatty and will make it easy to land right in the swamp if not tracked, are:

Oxtail from the upper part of the tail

Full-fat milk and full-fat yogurt

Any meat with visible fat

Chicken with the skin on

20% fat ground beef

Marrow bones

Cheese

Ribeye

Eggs

This isn’t to say not to eat those foods. Rather, if one of your meals on a certain day is built around one of the fattier proteins, it’s probably best to lower your fat in other meals to create a more balanced day of eating and avoid the “swamp.”

Tracking your macronutrient balance with Cronometer when eating these foods can help.

Balance Your Macronutrients

Avoiding eating both high-carb and high-fat can create the impression that you might have to either completely cut carbs or fats from your diet, or only eat carbs away from fats. A mentioned earlier, this is not true. Instead, the two should be combined in more of a balanced way. How to balance these and how your need for calories, carbs, fats and proteins varies depending on the time of day, will be covered in this section.

Follow The “Macronutrient Clock”

Did you know that our calorie needs and the need for different macronutrients vary according to the time of day? I decided to call this phenomenon the “Macronutrient Clock.”

This is another example of “how” we eat being almost as important, if not more important, than “what” we eat.

You could be eating all the “right” foods, but eating them at the wrong time during the day can make the difference between good health and weight maintenance vs. fat gain and unpleasant symptoms.

Our metabolism is at its highest in the first half of the day. As a result, our need for calories and carbs is highest in the first half of the day, at breakfast and during lunchtime. Giving the body plenty of calories early in the day helps to keep our metabolic engine running high for the rest of the day.

The morning is “carb time:” Our need for carbs is highest in the morning, to replenish liver glycogen, and give the body the energy to start the day.

Lunchtime is “protein time”: Our need for protein is highest midday, when we need a large, satiating meal that will carry us over into the afternoon.

The evening is “fat time:” Our need for fat is higher in the evening, when it can help slow down carb digestion so that we can maintain our blood sugar for 8 hours straight at night, getting a restful sleep.

If we deviate from what is best according to the “macronutrient clock,” the body doesn’t respond well. If our largest protein meal is in the evening, it will often interfere with sleep, making it hard to fall asleep or make our sleep restless. A breakfast that’s mostly fat will likely make us feel very sluggish. A lunch lacking in protein will have you hungry again in an hour or two.

Part of the reason why our tolerance for different macronutrients varies based on the time of day is the dance between thyroid hormones and melatonin, which follows a circadian rhythm.

Thyroid hormone levels are highest in the morning. They increase our tolerance and requirement for carbs and calories. Eating the bulk of our calories in the first half of the day means eating them when we are best equipped to burn them for energy. This is when our metabolism is at its highest.

Towards the evening, melatonin rises. Thyroid hormones and melatonin are like yin and yang. Thyroid hormones accelerate the metabolism, accelerate digestion, and help us turn carbs and calories into energy. Melatonin is anti-metabolic, slowing the metabolism, slowing digestion, and promoting the storing of fuel from food as fat.

If we eat most of our calories in the evening (think of the person who skips breakfast and lunch but eats a massive dinner), we are working against our natural rhythms. We are depriving the body of calories during the day, forcing it to slow the metabolism. We are then giving it a bulk of calories in the evening when it’s more primed for storing them as fat.

Even without changing what we eat, how and when we eat can be the deciding factor between burning the foods we eat for energy vs. storing them as fat.

How To Follow The “Macronutrient Clock”

As already mentioned, following the macronutrient clock doesn’t have to mean having breakfasts of nothing but fruit (although this does work well for many fat loss and energy wise), or eating nothing but fat in the evening. It is more about tweaking the macronutrient ratios of your meals slightly, depending on the time of day, and front-loading your calories (having the bulk of your calories in the first half of the day).

This could look like this:

Breakfast:

40 grams of rolled oats, cooked in 200 mL of skim milk, with 25 grams of honey, 8 grams of coconut oil, a pinch of salt, 10 grams of bloomed gelatin, and topped with 30 grams of dates and 60 grams of blueberries.

Calories: 519

Carbs: 89 g (65%) ← Most carb-heavy meal of the day percentage-wise.

Protein: 22 g (16%)

Fat: 11 g (19%)

Mid-Morning Snack:

Fruit shake with 100 grams of Skyr, 200 mL of orange juice, 100 mL of coconut water, 200 grams of mango, and 5 grams of coconut oil.

Calories: 334

Carbs: 58 g (66%)← Most carb-heavy snack of the day percentage-wise.

Protein: 13 g (11%)

Fat: 7 g (18%)

Lunch:

Shrimp curry made with 200 grams of shrimp cooked with bell peppers, oyster mushrooms and two tablespoons of yellow curry paste in 250 mL of light coconut milk. 300 grams of boiled rice, cooked in 250 mL of gelatinous broth.

Calories: 793 ← Highest calorie meal of the day. Together with the previous two meals, at this point, you’d have consumed about 65% of your total daily calories by mid-day.

Carbs: 104 g (55%)

Protein: 48 g (25%) ← the highest protein meal of the day percentage-wise

Fat: 18 g (20%)

Dinner:

80 grams of veal liver, tossed in rice flour and fried in 10 grams of ghee with sage. Two large baked apples on the side.

Calories: 510

Carbs: 73 g (52%)

Protein: 25 g (20%)

Fat: 16 g (27%) ← The fat content of the meal percentage-wise is increasing towards the latter half of the day.

Pre Bedtime Snack:

Papaya milkshake with 250 grams of fresh papaya, 300 mL of whole milk and 20 grams of honey.

Calories: 351

Carbs: 58 g (61%)

Protein: 11 g (13%) ← The protein content of the meal is lower before bed.

Fat: 10 g (26%) ← The fat content of the meal percentage-wise is higher in the latter half of the day.

As you see above, the tweaks are slight. Also, don’t let the above intimidate you, making you think that this all requires complicated calculations. In my opinion, once you become more embodied with your cravings and your body’s needs at different times of the day, getting the above balance “right” becomes somewhat intuitive.

You’ll likely crave more food and carbs in the morning when your energy requirements are higher. You’ll likely crave something protein-heavy and more substantial midday. In the evening, you might crave something that’s more “cozy,” both fat and carb-rich and lower in protein. Following these cravings can help you achieve the above balance somewhat naturally in your meals.

Be Consistent In Your Eating Habits

How would you feel if each month you had no idea how much your job was going to pay you until you got paid? “Will it be enough to cover my basic needs and then some, or will I struggle to pay rent?” Would this scenario stress you out? Most likely.

Well, your body also gets stressed out when it has no idea what to expect from you. Some people have the habit of bouncing between extremes: severely under-eating on some days and then eating way too much on other days.

If you eat 1,200 calories on a Monday but 2,500 on a Tuesday, and then 900 calories on a Wednesday, your body will have no clue what level of “metabolic speed” to adjust to. If you eat a low-calorie diet a few days in a row, everything (including your digestion) will slow down. Then, if all of a sudden you have a more “normal” day of eating, you’re sending this food into a body that’s not used to consistently processing that volume of food, leading to bloating, constipation and lethargy.

Eating nourishing foods won’t do much for you if your eating habits are inconsistent and all over the place. Be consistent. This means:

Eating the same or similar number of calories daily

Having your meals at similar times each day (for example, always having breakfast at 7 am and lunch at 12 pm)

Keeping the time intervals between meals pretty consistent (avoid having your meals every 3 hours on some days and every 10 hours on other days)

Having similarly-sized meals daily (try to not have a massive lunch some days and a tiny lunch other days)

Sticking to a similar macronutrient balance every day

Do Some Respond Differently Than Others to “Pro-Metabolic” Eating?

As mentioned earlier, assessing gut health, food intolerances, inflammation, carbohydrate tolerance and meeting the body where it’s at is important to figure out which foods are “pro-metabolic” for you.

However, sometimes food isn’t enough, especially if you were born hypothyroid or hypothyroidism has been epigenetically imprinted in your family for the last few generations. Stating that diet alone will be enough to get everyone back to a “youthful” metabolism is sadly just not true, and is not aligned with what Dr. Peat wrote about. There’s far more to health than food.

If someone had a childhood free from illness and their life (relationships, stress level, environment, job) is fulfilling, they can probably stay healthy and keep their metabolism high by eating whatever they please. If this person switches to a diet of highly nourishing foods, they will probably feel superhuman.

On the other hand, some people are just born very sick, and food isn’t always enough to fix all of that and restore a healthy metabolism. Other interventions, like targeted supplementation (of minerals or certain B vitamins), hormone supplementation (T3, progesterone, pregnenolone), certain medications (methylene blue, LDN, antimicrobials, dopaminergics), avoidance of endocrine disruptors, or even relocation to a better living environment and job change might be necessary to see drastic results.

Is Fat Gain Always Bad?

The last thing that I want to say is that, obviously, gaining excess body fat is bad.

That being said, while this might be controversial, I don’t think that fat gain is the most unhealthy thing that can happen to a person.

I think that it is far more unhealthy to be riddled with psychological issues (like anxieties, hallucinations, reactivity, excess emotionality and phobias), food obsession, body dysmorphia, immune suppression, fatigue, organ atrophy, premature reproductive failure and severe constipation, which are common consequences of chronic under-eating and excessive dieting.

Sometimes, a refeeding diet (where a person finally eats foods to satiety, following only their hunger ques and foregoing tracking) can be more appropriate than a slow reverse diet, especially when symptoms (physical or mental) are severe.

I myself pursued a refeed in the past as it was the right choice for me then. Doing so, after years of restrictive eating, helped me quite literally regain my sanity and get my brain back online, as well as finally fix my obsessive relationship with food (which wouldn’t have happened if I followed a slow reverse diet).

The refeed fat gain (that I then lost sustainably) was worth it, as the refeed itself was what I needed to move the needle on my health in places where it wasn’t budging.

I think it is common for very sick lean people who’ve been dieting for a long time to state that they refuse to eat more because they’d like to avoid fat gain for “health reasons.” I wish that those people would admit to themselves and others that what they’re really prioritizing is aesthetics, because the health consequences of long-term starvation are far more severe than the consequences of a small degree of fat gain.

At the end of the day, you need to choose what’s right for you. Hopefully, this article can help you make an informed choice.

In Conclusion…

Make changes gradually

Prioritize satiating foods

Don’t go overboard with fat

Increase your calories slowly

Be consistent in your eating habits

Eat most of your calories earlier in the day

Don’t eat foods that cause you unpleasant symptoms

Make carbs a priority in your meals in the first half of the day

Focus on getting enough calcium, B vitamins, magnesium, zinc, gelatin, vitamin K2 and selenium, while limiting PUFAs, plant defence chemicals and toxic metals

EXTRA RESOURCES

Additional resources, including:

Meal plans for different calorie levels (from 1,800 to 2,600 calories)

+ Simple instructions (recipes) to help you prepare the meals found within the meal plans

A video guide on how to use Cronometer

A guide for tracking biofeedback

A Q&A for any additional questions that I will cover in a supplemental podcast episode