Why the Carnivore Diet Helped Me at First...and Failed in the Long Run

Recounting my voyage into the world of dietary extremes

Hey, Kaya here. 👋 Welcome to my newsletter. I’m happy to have you here! Most of you arriving here likely know me from Instagram as @fundamental.nourishment

This is the very first post of my newsletter dedicated to nutritional heresy.

Heresy: opinion profoundly at odds with what is generally accepted

This post specifically is kind of like my “villain origin story,” if you will. It will start with a somewhat long-winded intro about my dietary journey beginnings, and what led me to question most of the accepted dogmas of the health and nutrition world. I hope that you enjoy this read and stay tuned for more. ❤️

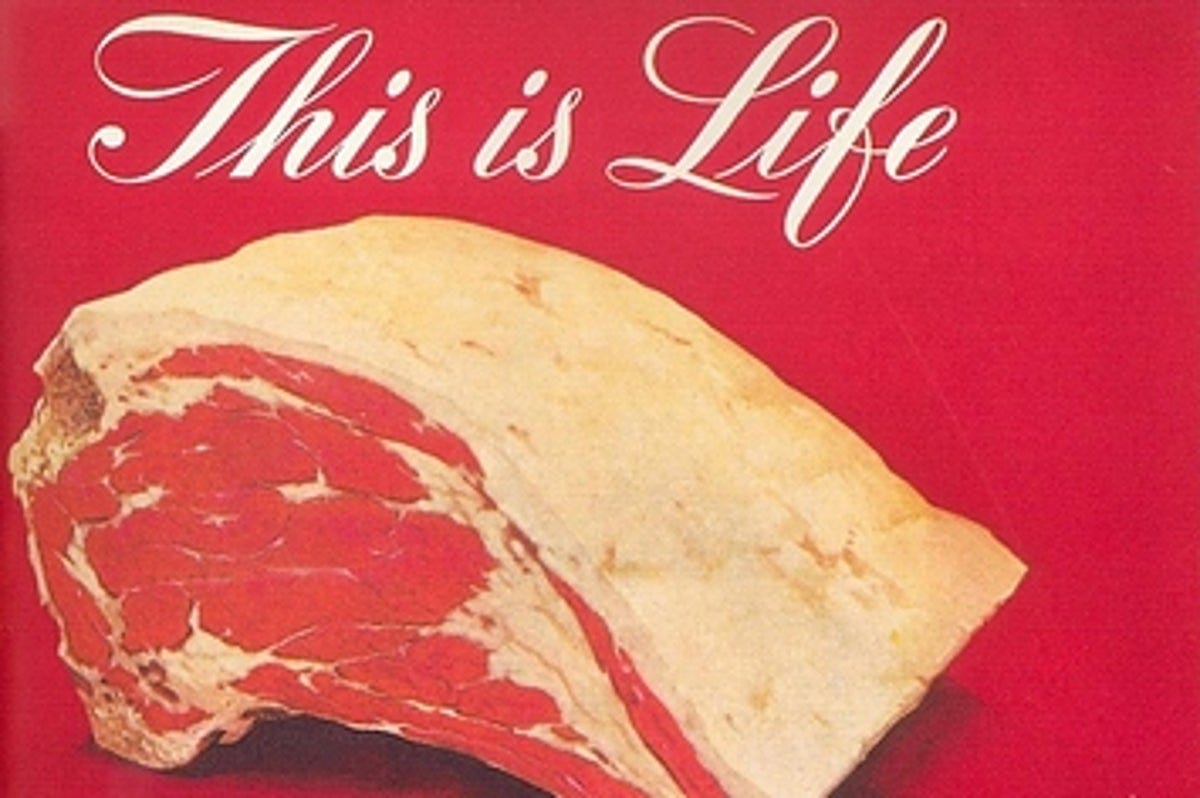

Having to tell people that I subside entirely on meat was a bizarre, hilarious and confusing time in my dietary journey.

But there was actually a reason for this madness. Or rather, a deep desperation with health problems that launched me into some extreme dietary fringes. So let’s back up. How did I even get to the point where I decided that this is a sensible way of eating?

My “healthy diet” flop: it started with Paleo…

My whole journey with the Paleo diet will be a topic for another post, but to paint the picture of how I tumbled down the carnivore rabbit hole, I need to start with a short overview of my Paleo journey.

I started the Paleo diet because I was dealing with some pretty scary health issues at the age of 21, which is the age when you’re supposed to be in your top shape. At the time, the Paleo diet seemed extremely logical to follow. Especially given that the “alternatives” to it when scouring the internet for information on how to eat better were either veganism or the food pyramid diet.

At the core of the Paleo ideology (at least the way in which it was popularly presented when I decided to partake) is the belief that in order to obtain good health we should eat as close as possible to how our “cavemen” ancestors ate. As part of our endeavour to eat like our prehistoric ancestors, we are to eat only what would have been available to us before we developed enough brain cells to learn how to mill grains into flour or milk a cow. Gluten (and grains in general) as well as dairy are strictly forbidden on the Paleo diet. Our Paleo plates should consist mostly of raw vegetables (the more the better), meat (including organs), eggs, nuts, seeds, and low-sugar fruit (on the assumption that as cavemen we had no access to high-carb foods.) By proxy, the Paleo diet is also a fairly low-carb diet. So, I basically started following a diet that most health nuts would have you follow: dairy-free, gluten-free, lots of raw vegetables, nuts, seeds, wild-caught fish and grass-fed meats.

I am tempted to go off on a tangent on how, in retrospect, I realize that not only does it really not matter what cavemen ate considering the vastly different world we live in, but how these assumptions of what cavemen ate are not even entirely based on facts. (On a side note, the fact that a diet ideology that preaches “eating like cavemen” is a-ok with nut butters, nut milks, almond flour breads and green smoothies is ironically hilarious to me.) Anyway, this rant should wait for my Paleo post.

I took a nosedive into the Paleo world. When you first cut out all the processed crap, noticeable improvements are granted. You start eating food and stop eating shit, so some things improve. But with time, when eating foods that are not supportive of human physiology, even if these foods are “real foods,” things start to go south.

The short version of the story goes like this - while Paleo seemed to help with some things at first, after about a year, my thyroid health and gut health seemed to be in a far worse state than before my Paleo journey.

For some time, I’ve suspected hypothyroidism, but my concerns were met with dismissal from conventional doctors who continued to reassure me that my thyroid blood tests were “perfectly in range” (a statement that I now know means absolute baloney). This led me to convince myself that having to wear a jacket indoors when others are wearing t-shirts is completely normal and that I’m just too much in my head about all of this. Since I was eating a diet that was widely considered extremely healthy, I didn’t know what else I could possibly do to improve my health. According to the information that I was able to gather back then, I should have been in top shape health-wise eating the whole-foods diet that I was eating. Some would have claimed developing superpowers to be imminent.

Anyway…

Considering my poor health throughout life, I thought I was still in “okay” shape. If you don’t know what healthy looks/feels like, then you have no baseline to strive towards. This illusion was shattered once I lost my menstrual cycle, which is a massive cry for help from the body, especially in your early 20s.

At that point, I decided to seek out the help of a naturopathic doctor. I told her about the loss of my menstrual cycle, awful moods, being cold, and all the other low-thyroid “fun” that I was experiencing. The good that came out of the visit was that she confirmed that I had the thyroid health of a 70-year-old grandma, or, in other words, I was highly hypothyroid. This diagnosis was not surprising to me at all, but getting validation from an “expert” helped me feel that I wasn’t crazy. The disempowering part of the visit came when I described my diet to my then-naturopath and her response was that “my diet is perfect.” Considering my once very perfectionist, type-A personality and that I tried to follow the Paleo diet as perfectly as possible I said to myself “duh, of course it is!” Sadly, this did not leave me with much room to maneuver. “What could possibly be messing me up so badly if, according to this ‘holistic expert,’ what I’m already doing is perfect?” Sure, she did recommend some things that I wasn’t doing, such as castor oil packs and “a sensory deprivation tank to be less stressed.” Although I was sure that I was not suffering from a float tank deficiency, I thought to myself “why not try it,” especially since at the time I happened to live in a city where float tanks were available, and through a fluke of luck I found an active deal on Groupon for a one-time float session for $10. The float tank experience was fun, and by bamboozling Groupon with different e-mail addresses and showing up whenever a different employee was working, I did my “one-time” float session about 5 times. Despite the fun experience, none of my issues improved. But hey, now I could at least say that I’ve done a sensory deprivation tank.

My descent into the world of carnivory

Being told that what I’m already doing is “perfect” was really messing with my head as it made zero sense to me that at 23 I’d be having symptoms not far off from menopause while doing everything “perfectly.” I was already deeply immersed in the “holistic” space back then so I knew that “genetics” wasn’t the reason, as most of the time genetics is used as a scapegoat explanation when someone has no clue what is actually going wrong.

Of course, knowing that low thyroid function was, in fact, what was wrong with me, I went down the path of independently investigating dietary and lifestyle approaches focused on restoring thyroid function. I was disappointed to see that many of the online holistic thyroid “experts” that I discovered at the time recommended kale smoothies, cutting out dairy and replacing it with nut milks, “avoiding inflammatory sugar,” and all the other dietary silliness that I was already partaking in and that was (unbeknownst to me at the time) contributing to my metabolic issues. Sure, some of the advice was good, such as “rest more.” But no amount of hot baths and exercise breaks seemed to have much of an effect on improving my well-being. My disappointment and confusion persisted.

One day while exploring the great abyss that is YouTube, I came across something that I have never heard of before – the carnivore diet, aka a diet of nothing but animal products. I was intrigued. Mostly, because it’s an idea that I haven’t heard of prior and one that sounded absolutely outlandish (although around the time of me discovering it, it started becoming quite trendy, with big names such as Jordan Peterson and his daughter Mikhaila partaking in it.) Considering that what I was doing was clearly not working and that any info that I found was just more of what already wasn’t working for me, I was 100% ready to jump into anything that sounded new and outlandish. Besides, in my world, there’s no better way to find out whether something works or not than through experimentation.

“Vegetables are bad for you?”

The most captivating argument of the carnivore-sphere was that vegetables (especially raw vegetables) might actually be quite detrimental to our health (I’ll get back to the likely controversial “vegetables are bad for you” topic and my current take on it later in the article).

This made a lot of sense to me. Many times in my Paleo days I sat there wondering “How could raw kale possibly be good for us if all of our senses tell us to stay as far away from it as possible?” It tastes horrible and it smells like nothing. How would our “cavemen” ancestors have known that this is food if no feature of it screams “hey, I’m nutritious and delicious, eat me!” However, these valid concerns stemming from intuition and common sense would be dismissed by me looking up nutrition data and swiftly convincing myself that a food that appears to be such a nutritional “powerhouse” on paper must indeed be a nutritional gift sent from heaven.

After going down the rabbit hole on anti-nutrients, “plant toxins,” and “plant defence chemicals” I learned that certain plant compounds can inhibit thyroid function and that the nutritional value of vegetables “on paper” does not represent “bioavailability,” aka our ability to actually absorb and/or utilize those nutrients.

After learning about how I might have been bamboozled by the “eat your greens” rhetoric, I felt pretty betrayed because I have just spent 2 years overriding my natural instincts, forcing myself to eat massive salads, heaps of raw vegetables, and green smoothies that I hated, in hopes of improving my health, just to see it go more downhill. Before my Paleo days, I was the world’s number 1 raw vegetable hater. Watching someone eat a salad was the most perplexing thing to me, as I could not understand how they could be willingly subjecting themselves to such torture. Actually, it wasn’t until I was 18 years old that I first managed to override my natural, protective instincts and force myself to eat my first raw vegetable (mostly due to peer pressure). Growing up, whenever I was invited to a friend’s place for dinner, their parents would watch in horror as I’d blatantly push the undercooked or raw vegetables served to me as far away from my plate as possible, and I would be in horror of how someone could actually eat this stuff. I recall my friend’s mom asking me “How are you not dead yet if you’ve gotten 0 vitamins in your life?” – in reference to my born-in refusal to eat raw or undercooked vegetables. Back then, in my teenage rage, I’d just think to myself “Honestly, not sure, but the fear of death is still not enough to make me eat this stuff.” Now, I finally received some validation, after convincing myself that “vegetables can’t be an issue because vegetables are good for you” for far too long.

Waving “goodbye” to veggies

I decided to massively cut down on my vegetable intake, leaving only sweet potatoes, berries, avocados and squashes as the only parts of the “plant kingdom” in my diet. I felt much better and this would be a pretty okay diet, but my poor gut was in such a dire state after my Paleo escapade, that even squashes and sweet potatoes would leave me incredibly bloated.

I realize now, in retrospect, that what I was dealing with was a nasty bacterial overgrowth (something that often happens in part as a consequence of hypothyroidism), and replacing sweet potatoes with simple sugars such as honey, white rice or maple syrup would have alleviated the problem. However, hindsight is 20:20, and I did not have the knowledge that I have now back then. Instead, I fell prey to the most detrimental (in my opinion) aspect of the carnivore ideology – zero-carb. I allowed myself to get convinced that my digestive issues are there because I still have some carbs in the diet and carbs are a sure way to “feed candida” and develop horrible digestive issues. Honestly, back then, it was not that hard to convince me that carbs are “evil.” I was coming from a Paleo background (where carbs are already demonized), and after a lifetime of hearing both the mainstream and alternative health spheres call sugar a “white devil” that will give you cancer and diabetes, it was unthinkable to me at the time that plain sugar might be exactly what my poor digestion needed.

At that point, once again, I should have listened to common sense and asked myself “if carbs are the sole reason for all evil then how come all of Italy hasn’t gone extinct?” Instead, I decided to cut out all the plants, having trace amounts of carbs enter my diet from the occasional raw milk that I reintroduced as part of my “carnivore experiment” (which I later started fermenting to reduce my carbohydrate intake even further).

Anywho, I became extremely fascinated by the concepts behind the “animal foods only” way of eating (especially since I saw some immediate improvements in my health), which led me to research and learn about this new paradigm as much as possible. This has exposed me to certain nutritional schools of thought and the work of certain health educators that I still find very valid to this day, including the works of Dr. Weston A. Price, Dr. Natasha Campbell-McBride, and many of the great talks from the Ancestral Health Symposium.

For the next 9 months, I followed a diet consisting of meat, eggs and dairy, a great chunk of it raw (I’ll cover the concept of raw animal foods in another article). Read on to see what happened.

The results of my carnivore experiment

The good

The most immediate improvement after starting an “animal products only” diet was complete relief from digestive issues. Here’s the thing - I did not even realize how awful my digestive issues were until they disappeared. Digestion wasn’t even the main thing that I was after fixing. I didn’t realize how badly it needed fixing until I felt, for the first time, what it’s like to not be in some degree of discomfort after a meal. The concept of eating a meal and feeling light and energized afterwards, without intense bloating and gas, was a foreign concept to me. Although my two years of raw veggie overload made my digestive issues markedly worse, especially near the end of those two years, my digestion was never good to begin with. Imagine my surprise when I realized that one can actually eat a meal and not feel like a gas balloon afterwards.

The relief from digestive pain came with some other additional benefits, such as better alertness and less brain fog, even though during this time I decided to cut out coffee.

Although I skimmed over this part earlier, as part of my carnivore experiment I reintroduced dairy into my diet. This was actually something that I was extremely reluctant towards at first after two years of being dairy-free and after consuming (heh) all the Paleo content that convinced me that “inflammatory” dairy would worsen my existing hormonal issues. One of my biggest concerns was my skin. My skin has always been very acne prone, and it never got much better on my gluten-free, dairy-free Paleo regimen.

I reintroduced dairy starting with raw goat milk. A whole litre of it in one sitting – I did not go slow. The results? My newfound relief from digestive issues was unaffected. No bloating, no gas. More so, during the entirety of my 9-month carnivore experiment, my skin became the clearest that it has ever been. I’m actually extremely happy that I decided to include dairy in my carnivore experiment, as with (nearly) all other foods eliminated, it showed me that dairy is in fact not a trigger for my hormonal, digestive or skin disturbances at all.

What about my thyroid health? Surprisingly, that improved as well (at first at least). My period came back (hooray!) and my hair, which has refused to grow past my shoulders since the age of 14, finally grew to around my mid-back. I actually had quite a few people around this time ask me “Have you been using a new shampoo?” just to see them scratch their heads when I said, “No new shampoo, just eating more eggs.” My waking insomnia (when you wake up at 3 am and can’t fall back asleep) that has been plaguing me for a few months while still on Paleo also disappeared. Interestingly enough, during my first few months on carnivore (what I now call my “carnivore honeymoon period”), my sleep was impeccable.

How can one explain these results?

Most of those that end up on the carnivore side of the dietary coin are actually ex-vegans who developed various health issues on the vegan diet, and with new-found dismay for any foods from the plant kingdom, decided to switch over to the polar opposite of dietary ideologies. My story is a bit different in that I’ve never been a vegan or vegetarian. Actually, I don’t think I’ve ever even gone a day without meat.

Most of the benefits of the carnivore diet are attributed to fixing vitamin deficiencies by reintroducing vitamins only found in animal products (such as retinol, real vitamin B12, K2-MK4, creatine, heme-iron, taurine, etc.) into the diets of those who have subsided on plant-only diets for a long time. I do think that this is a major factor in the betterment of those coming from plant-based backgrounds, as adding eggs and organ meats such as liver into the diet will provide an abundance of nutrients that are not obtainable when plant-based. Heck, even reversing a protein deficiency can be the reason why some feel much better, as low protein intake can mess up one’s health in a number of ways.

In my case, I was already coming off of a high protein diet, where I was consuming foods such as eggs and various organs, such as liver, kidneys, tongue, etc. The improvements in my health were not from reintroducing animal products but from cutting out plants – mainly vegetables.

There are a few factors to cover when it comes to the mechanisms behind why cutting out vegetables seemed to work well for me. Namely - plant defence chemicals, bacterial endotoxin and fibre excess.

Let’s start with plant defence chemicals and “anti-nutrients.” These are chemical compounds that plants use to defend themselves and ensure their own survival.

Animals have various methods of defending themselves from predators – speed, strength, claws, and sharp teeth. Plants don’t have these physical capabilities. In order to survive they had to develop other ways to fend off insects, fungi and even mammals, including herbivores. To do so, plants employ chemical warfare. Plant toxins, such as tannins, lectins, trypsin-inhibitors, oxalates, goitrogens, and plant pesticides (yes, plants make their own pesticides, which can be quite toxic) can prevent potential predators from being able to digest and absorb the vitamins and minerals stored in plants, inhibit the release of stomach acid and digestive enzymes, disrupt the hormonal profile of the animal eating them, or, in large enough amounts, poison the animal, causing organ failure and death. (Also, stressful growing conditions can cause plants to produce more toxins in response to the stress, and to communicate to other plants to do the same).

Animal senses (including those of humans) evolved to keep us safe from potential poisons.

Ruminants, such as cows, have a 4-compartment bacteria-filled rumen specialized in fermenting and neutralizing plant toxins. (For reference, humans do not have a rumen. We have an acidic bacteria-free stomach, similar to cats, dogs and vultures). When free-roaming, ruminants rely on their senses to avoid an excess of potentially poisonous plants. However, even these animals, which are equipped with plant-toxin-neutralizing hardware, can become poisoned when locked in a pan with a limited variety of plants, whereby they override their instincts and end up consuming whatever is available, even if their instincts tell them otherwise. Cows tend to find herbs that are poisonous to them, such as lupine or black nightshade, unpalatable. They would not normally eat them unless their hay is contaminated with them or they lack other feed. Severe poisoning can result in paralysis, coma or even death.1 Sheep, which are incredible plant-toxins neutralizers, can experience goitre, thyroid dysfunction, stillbirths and congenital hypothyroidism when fed an excess of kale.2

A table showing thyroid enlargement (goitre) in lambs fed predominantly kale vs. those on pasture that got to choose the herbs that they ate.

This here is a great presentation on plant toxins, if you’re curious to learn more.

While we don’t have rumens, we have big brains. Thanks to our big brains, we know how to cook and peel vegetables. There is a reason why well-cooked kale tastes better than raw, and why a peeled carrot tastes better than an unpeeled carrot. Cooking degrades many of the plant toxins, as does discarding the peel, where many of the plant defence chemicals are concentrated.

When, as humans, we are repelled by certain vegetables, it is not because we are weak-willed and hate “healthy food.” It’s because we are trying to not get poisoned. Babies and toddlers, unlike adults, have not had their instincts trained out of them, and they are naturally repelled by certain vegetables, especially raw. Unfortunately, we have fallen prey to the nutritional dogma that constantly advocates for the vitamin content of vegetables (NOT their bioavailability though), but seems to turn a complete blind eye towards their content of plant toxins and the role of plant toxins in various diseases.

Certain individuals are more susceptible to plant toxins than others. Our senses are usually a great guide for this. Since my senses have always repelled me from vegetables big-time, I am sure I am on the “more susceptible” side.

As per thyroid health, many vegetables, including broccoli, kale, cauliflower, rutabaga, turnip, and root cassava contain plant toxins called goitrogens (again, goitrogens are higher in raw vegetables). Goitrogens inhibit iodine utilization, hindering the production of both the thyroid prohormone T4 and the active thyroid hormone T3.3 Goitrogens also increase the pituitary hormone TSH, an elevation of which can drive systemic inflammation.4 While goitrogens are the main offenders in terms of thyroid health, there are many compounds in the plant kingdom that can interfere with thyroid function in many ways, namely through burdening the liver, which is the main site of T4 to T3 conversion.

Speaking of the liver…let’s talk about bacterial endotoxin.

What is endotoxin? As the name implies, endotoxins are toxins. These toxins are released when gram-negative bacteria in our digestive tract die or divide. While not all the bacteria that constitute our microbiome are gram-negative, some are.

“Endotoxin is a lipopolysaccharide component of the Gram-negative bacteria cell and is released during active cellular growth and after cell lysis. While it is not an infectious particle, endotoxin is biologically active material derived from bacteria that can affect many human organ systems and disrupt humoral and cellular host mediation systems.”5

Our microbiome is located in the large intestine. The large intestine is the only place in our body where we can break down plant fibres via bacterial fermentation. In other words, most raw vegetables that we eat will be digested by bacteria in the large intestine.

“Dietary fiber is not hydrolyzed by human digestive enzymes, but it is acted upon by gut microbes.”6

The more that we feed the bacteria in our guts, the more they grow and divide. The more that they grow and divide, the more potential for endotoxin production, especially if we house more of the gram-negative bacteria in our guts.

Also, it goes without saying that bacterial fermentation can produce gas that can lead to bloating and intestinal discomfort, especially if we are housing rather pathogenic bacterial strains and/or if dealing with bacterial overgrowth.

Stressors such as strenuous physical activity, emotional stress, or even excessive bacterial activity, can injure the gut lining. When our gut becomes injured, bacterial endotoxin can flow out of the gut and make its way to the liver, burdening the liver and negatively impacting our metabolism and our hormonal health.

“Endotoxin, one of the components of the outer wall of gram-negative bacteria, is released by the microbiota in the gut and is directly introduced into the liver via portal blood”7

Low thyroid function can make the liver more prone to injury by bacterial endotoxin, and a burdened liver further lowers metabolic function via a negative feedback loop. This is because the liver is responsible for converting thyroid pro-hormone T4 to the active thyroid hormone T3.8 When the liver is strained, the synthesis of the active thyroid hormone is negatively affected. (My T4 to T3 conversion was particularly negatively affected during this time, as per the blood work that I had done).

More than that, bacterial endotoxin has been shown to be directly involved in the development of autoimmune thyroiditis.9

When it comes to hormonal health, bacterial endotoxin has the ability to inhibit the glucuronidation system10, hindering our ability to detoxify estrogen, and making estrogen dominance more likely.

Bacterial endotoxin can also inhibit mitochondrial respiration 11(the cell’s ability to make energy in the form of ATP). ATP is needed to facilitate the conversion of cholesterol into downstream sex hormones such as pregnenolone, progesterone and DHEA. A deficiency of these hormones can lead to a loss of the menstrual cycle.

Limiting bacterial activity would also explain why my mood and brain fog improved so much. While I do believe that these effects can often be due to a rise in stress hormones caused by a deficiency of carbs in the diet (more on this in a bit), I believe that in my case the immediate improvement in my mood was due to lower serotonin levels. Although praised in the mainstream as the “happy hormone” (although there is plenty of evidence that serotonin is anything but that), excess serotonin can actually lead to lethargy and reduced cognitive function, among other unpleasant symptoms12. 95% of the neurotransmitter serotonin is produced in the gut as a result of bacterial activity, and endotoxin and serotonin have an agonistic relationship - they potentiate one another.

The carnivore diet takes away any foods that can feed bacteria, the top offender being foods high in soluble fibre. This tends to provide relief from conditions caused by excessive bacterial activity, endotoxin and high serotonin. Removing plant fibres can also, with time, decrease certain bacterial populations. Again, while much of the nutritional thinking out there focuses on increasing the intake of prebiotic and probiotic foods to increase our populations of potentially good bacteria, it ignores the fact that even certain bacteria that are regarded as “good” in the mainstream view can produce endotoxin, that excessive activity of any bacteria can still injure the gut and produce excess serotonin, or that more harmful strains of bacteria can often feed on many of the prebiotic foods.

The intense focus on increasing microbiome diversity ignores the research on the other side of the coin - the benefits of being germ-free. For example, research done starting around the 1950s on entirely germ-free animals showed their profound resilience to liver disease as compared to conventional, microbiome-having animals.13 14

I theorize that the carnivore diet alleviated my digestive issues and provided relief from hormonal issues by minimizing gut injury and reducing bacterial endotoxin (which can strain the liver), as well as reducing serotonin, which, in excess, acts like a limiter of metabolic function, limiting ATP production and shifting us more towards a “hibernating” metabolic state15.

As mentioned, I believe that the consequences of excessive fibre consumption are rarely talked about. I don’t think that fibre is all bad. It can be beneficial in helping us remove old bile. Certain insoluble fibres, such as fibre from raw carrots, can actually have an anti-bacterial effect and the ability to remove excess serotonin, endotoxin and estrogen from the gut. However, even the non-fermentable, anti-bacterial fibres can become a problem in excess. And I think it’s important to talk about this as most of the nutritional messaging that many of us are met with focuses on indiscriminately encouraging us to increase fibre intake.

Excess insoluble fibre can bind to fat-soluble vitamins and cholesterol. While widely and wrongly demonized, cholesterol is the building block of all of our sex hormones. Fat-soluble vitamins, such as retinol, are also needed for the synthesis of hormones such as progesterone (the anti-estrogen hormone) and T3 (active thyroid hormone). When excess fibre is consumed, it can create a hormone deficiency by binding up the building blocks needed for hormone creation. Some research indicates that consuming too much fibre can lead to a lack of ovulation.

“Dietary fiber consumption was inversely associated with hormone concentrations (estradiol, progesterone, LH, and FSH; P < 0.05) and positively associated with the risk of anovulation (P = 0.003) by using random-effects models with adjustment for total calories, age, race, and vitamin E intake. Each 5-g/d increase in total fiber intake was associated with a 1.78-fold increased risk (95% CI: 1.11, 2.84) of an anovulatory cycle. The adjusted odds ratio of 5 g fruit fiber/d was 3.05 (95% CI: 1.07, 8.71). […] These findings suggest that a diet high in fiber is significantly associated with decreased hormone concentrations and a higher probability of anovulation.”16

Anyway, as I am writing this, I am realizing that this section is quite long. However, I really wanted to present the arguments as to why I believe the carnivore diet offered some immediate health improvements for me and explain the mechanisms behind it. I think that understanding the “why” behind why something works is extremely important when trying to understand health. I also think that the downsides of vegetable consumption are rarely discussed and I could see how if this section was missing, the benefits that I obtained from cutting out plant foods might have been extremely perplexing to a reader who has only ever heard of the benefits of raw vegetable consumption prior to reading this.

Now that the mechanisms behind “the good” part of my carnivore experiment are explained, let’s jump into “the bad,” and the mechanisms, or, the “why” behind it.

The bad

Now, my carnivore experiment was not all steak-flavoured rainbows and butterflies.

As I said, there was a honeymoon period where I saw some marked and immediate improvements that quickly made me a devoted follower of the carnivore ideology. I was drinking the Kool-Aid.

But – under the bliss of my newly-discovered painless intestines and luscious hair, certain brand-new and quite odd symptoms were breaking through the cracks.

After about a month or so after adopting the “no plants allowed” diet, I started noticing calculus/tartar buildup on my teeth. I have now learned that this is a visible sign of a deeper and scarier issue.

Tartar buildup on teeth is often a sign that calcium is being deposited in soft tissues as opposed to in bones where it belongs. While tartar buildup on teeth is quite an unpleasant cosmetic symptom, it is an indicator that calcium deposits can be happening elsewhere too, such as in veins and cells, where they become a serious issue.

What is behind this phenomenon? The following three aspects of the carnivore diet can play into this phenomenon:

Low calcium-to-phosphorous ratio

Lack of dietary fructose

Overall lack of dietary sugars (carbohydrates)

Low calcium-to-phosphorous ratio

Although this might sound a bit counter-intuitive, calcium deposits in soft tissues happen when a person’s diet is low in calcium, as opposed to high in calcium, especially in proportion to the mineral phosphorous.

As you might remember, I reintroduced dairy into my diet, and although dairy is known for its high calcium content, it’s also quite high in the mineral phosphorous. As such, milk contains approximately a 1.3:1 calcium-to-phosphorous ratio. Meat, which made up the rest of my diet, is very high in phosphorous, while only containing trace amounts of calcium. So, in short, on a diet of mostly meat, my calcium intake was much lower in proportion to my intake of phosphorous.

A deficiency of dietary calcium, resulting in low blood calcium, triggers the release of PTH (parathyroid hormone). PTH removes calcium from bones to increase blood calcium and can lead to calcium being redistributed into soft tissues.17

Similar to a calcium deficiency, a phosphorous excess also increases PTH, resulting in the same phenomenon. Lowering the amount of phosphate in the blood lowers PTH.18

“Ca [calcium] and P [phosphorous] are both essential nutrients for bone and are known to affect one of the most important regulators of bone metabolism, parathyroid hormone (PTH). Too ample a P intake, typical of Western diets, could be deleterious to bone through the increased PTH secretion. Few controlled dose-response studies are available on the effects of high P intake in man. We studied the short-term effects of four P doses on Ca and bone metabolism in fourteen healthy women, 20-28 years of age, who were randomized to four controlled study days; thus each study subject served as her own control. P supplement doses of 0 (placebo), 250, 750 or 1500 mg were taken, divided into three doses during the study day. The meals served were exactly the same during each study day and provided 495 mg P and 250 mg Ca. The P doses affected the serum PTH (S-PTH) in a dose-dependent manner (P=0.0005). There was a decrease in serum ionized Ca concentration only in the highest P dose (P=0.004). The marker of bone formation, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, decreased (P=0.05) and the bone resorption marker, N-terminal telopeptide of collagen type I, increased in response to the P doses (P=0.05). This controlled dose-response study showed that P has a dose-dependent effect on S-PTH and increases PTH secretion significantly when Ca intake is low. Acutely high P intake adversely affects bone metabolism by decreasing bone formation and increasing bone resorption, as indicated by the bone metabolism markers.”19

Considering that my daily diet back then looked something like: 400 grams of steak, 300 ml of soured milk, 3 eggs, 50 grams of butter and 50 grams of liver, that would be about an 8.6:1 phosphorous to calcium ratio (damn!). The optimal ratio, when it comes to minimizing PTH secretion is around 1:2 P to Ca.

Lack of dietary fructose

Fructose gets a bad name, but, as I’ve learned, it’s actually essential to many enzymatic processes in the body. I will write a separate article devoted specifically to fructose.

One of the ways in which fructose is helpful is in maintaining a favourable calcium-to-phosphorous ratio. While fructose-containing foods, such as fruit, culinary fruit (such as squashes), honey, and white sugar contain a varied amount of calcium and phosphorous, fructose itself inhibits the small intestine from absorbing excess phosphate.20 A higher intake of fructose has actually been seen to increase calcium accumulation while lowering phosphate accumulation.21

Overall lack of dietary sugars (carbohydrates)

Despite what every keto guru might want you to think, sugar is actually good for you. Not a typo, you read that right, and it took me years of low-carbing to finally admit that. Although I will not cover the many benefits of sugar in this article, I will cover why dietary carbohydrates are crucial for optimal hormonal health, as I am convinced that lack of dietary carbohydrates is the number 1 most detrimental aspect of the carnivore diet.

But first, let’s get back to the tartar buildup on my teeth. What do carbs have to do with it? Well, as mentioned, elevated PTH is what causes calcium to be pulled out of bones and into soft tissues. Excess dietary phosphorous, and a low calcium intake relative to phosphorous will increase PTH. But…lack of carbohydrates in the diet also increases PTH.

How? Well, low-carb diets cause an elevation of cortisol. Cortisol is a hormone produced by the adrenal glands. It is part of the “emergency” or “stress” cascade of hormones. Cortisol directly stimulates the increase in PTH. Why do low-carb diets increase cortisol? Let me explain.

Cortisol is there to help you maintain blood sugar, especially in acute situations when you need lots of energy but are unable to eat (such as when being chased by a tiger). If this state becomes chronic (such as when choosing to stay alive when eating zero carbs), cortisol will upregulate the production of glucagon. See, even if a person decides to go “zero-carb,” the body still needs sugar. If blood sugar drops below 50, a person can go into a coma and die. To maintain stable blood sugar while eating zero sugar and experience 0 negative consequences, we would need to have a magic fairy that can create sugar out of thin air. However, the closest thing to magic fairies that we have to ensure our survival are our “emergency hormones,” such as cortisol and glucagon. But these hormones can’t just create sugar out of thin air. They have to create it out of something, and this “emergency response” comes with consequences. If sugar is not coming in from the diet, cortisol and glucagon need to break down proteins and fats to create it through a process known as gluconeogenesis. These proteins can include your own tissues (such as muscles, skin, and lastly organs).

I experienced the negative effects of gluconeogenesis when eating high-fat/low-carb, realizing that no matter how much protein I tried to eat, it was impossible for me to build muscle when resistance training on the carnivore diet, and whenever I did train, I smelt like ammonia. These are direct signs that my body was eating its muscles as opposed to building them up. And no, I was not in a caloric deficit, and I was not overtraining, but I was unable to put on muscle, yet gained body fat rapidly!

And here’s another kicker. Guess which hormone is responsible for stimulating gluconeogenesis, together with the other “emergency hormones”? PTH.22 PTH elevates to stimulate gluconeogenesis because all the hormones of the “emergency response” (aka when the body is in some level of suboptimal state) work together.

Blood sugar balance aside, gluconeogenesis remains constantly upregulated when on a low-carb or zero-carb diet as certain cells can’t run on fat.

For example, to create sugar for the brain because the brain can’t be sustained on fat alone. Why? Well, unlike oxidizing glucose, oxidizing fats results in the creation of far more reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS are highly reactive chemicals that can damage and kill cells when unopposed. (This is why antioxidants have gained their fame - they help to control ROS. However, the brain has a low capacity of antioxidant enzymes). The brain is too important to risk damaging, and since neural cells have a low capacity for regeneration if injured, sugar has to be the primary fuel for neural cells.23

All of this doesn’t sound so good, does it? Nope, it doesn’t. And it takes me to the 2nd part of my negative effects from the carnivore diet, titled…

Why low-carb diets are horrible for your hormones

Although during my carnivore “honeymoon period” the reduction in endotoxin and plant defence chemicals allowed me to experience some immediate improvements in my thyroid function (indicated by a return of my menstrual cycle, more hair growth, and better sleep), this soon fizzled out, and my thyroid function started to steadily decrease once again. My hair stopped growing, my period started coming with more and more of a delay each month, and although I had little issues with regular bowel movements in the first couple of months of my carnivore experiment, soon my bowel frequency reduced to less than once per week. Although few are aware of this, thyroid function is the main “controller” of bowel frequency, and constipation is a key sign of poor thyroid health. I also started feeling much less resilient to stress, as it became much easier for me to cry, with daily tasks starting to seem impossible. Thyroid hormones oppose stress hormones and our thyroid function dictates in part our resilience to stress. Also, as briefly mentioned already, I gained a lot of fat, really fast, while eating relatively the same amount of calories as on Paleo. Sure, some of it was definitely due to the fact that the calories in animal foods are much easier for the body to break down and absorb than calories from raw plants. Still, this should not have accounted for the 20 lbs that I gained in the span of about 2 months. It was a clear sign that my metabolism slowed further. On a side note, this weight gain caused me to experience a lot of “I’m sure you’re eating carbs and lying about it” shaming in carnivore forums and Facebook groups, where the only advice ever for weight struggles was “start eating less” (even if the person was already eating 1,600 calories or less), and the only advice for any health problem experienced on the diet was “eat more meat.”

I later learned that carbohydrate restriction is one of the worst things that a person can do for their thyroid health.

Most cells in the body prefer glucose as their primary fuel source. When the body has to keep relying on the “emergency hormones” to create its own sugar, this signals to the body that it’s in a suboptimal environment that cannot provide the substrate that the cells prefer. As such, over time, metabolism will slow down to adapt to the perceived “hostile environment.”

The body is made up of different cells with different preferences. Something that few are aware of is that the body burns both glucose and fat at all times. However, glucose is the main source of energy, preferred by most cells. Certain glucose-preferring cells can switch to burning fat for fuel, however, this directly causes the metabolic rate to decrease. How? Let’s talk CO2.

Burning fats for energy produces 50% less CO2 than burning carbs. Despite the common belief to the contrary, CO2 is not a waste product and it is needed to get oxygen from the blood into the cells, through a mechanism known as the Bohr Effect. In short, the Bohr Effect works something like this – a red blood cell will give the oxygen molecule that it’s carrying to the tissue cell if the tissue cell gives it a CO2 molecule in return, in a sort of trade transaction.

Without enough CO2, cells can’t get enough oxygen. Cells need oxygen to produce energy. Low cellular oxygen = less ATP production = low cellular energy.24 Cellular energy is needed for all “the chemical processes that occur within a living organism to maintain life” (aka, metabolism). Low cellular energy = low metabolism.

“As a result of hypoxia, ATP levels drop, cellular functions cannot be maintained, and – if the insult lasts long enough – cells die.”25

On a bit of a side note, in relation to the phosphorous/PTH part from earlier, CO2 can increase the absorption and retention of calcium while increasing the excretion of phosphate. 2627

We can see this metabolism-lowering effect of chronically relying on “emergency hormones” in the fact that many long-term keto-dieters end up with low T3 and high cholesterol. It is actually a known fact at this point that keto diets decrease T3, the active thyroid hormone.

“While there are variations in participant demographics and study designs, the general outcome seems to be that carbohydrate restriction, or nutritional ketosis, results in a shift in the ratio of circulating thyroid hormones, without a change in TSH, with an increase in circulating inactive T4, and a reduction in active T3.”28

There is an inverse correlation between the emergency hormones and thyroid hormones. This means that whenever we are in a state where adrenal-hypothalamus-pituitary hormones like PTH, cortisol and adrenaline are elevated, active thyroid hormone will be decreased. “Emergency hormones” such as adrenaline29, glucagon 30 and cortisol31 decrease the conversion of T4 to T3 in the liver. T3 increases mitochondrial ATP production32. ATP is needed to convert cholesterol to sex hormones (and high blood cholesterol has more to do with low thyroid function than it does with cholesterol consumption – cholesterol blood tests used to be used to diagnose hypothyroidism back in the day). And thus…low T3 = low metabolism = high cholesterol = low sex hormones.

Certain keto advocates are aware that low-carb diets lower T3, but they state that -

“On a ketogenic diet, you don't need as much T3 because you're not spiking glucose from eating carbohydrates, and you need less T3 because there’s less glucose to metabolize.”

This statement reduces the importance of T3 solely to its role in sugar metabolism, completely ignoring the role that T3 plays not only in sex hormone synthesis but also in supporting healthy heart function, digestive health, bone health, and really the health of every single system in the body, as every function is dependent on ATP, the synthesis of which depends on T3.

Stress hormones are part of the reason why those who go keto/carnivore (such as myself in the past) feel unstoppable at first. At least for some time. In reality, it’s just a chronic state of fight or flight. A state that’s meant to be acute, as it’d designed to give you an abundance of short-term energy to escape from a predator, in part by eating your own body. However, when this state is chronic, you never have the chance to rebuild the damage. This is why those of us that make it to "end-stage low carb" start experiencing lots of “low energy symptoms” as the body slows down to preserve itself and make it through the “unfavourable conditions.”

Cramps, cramps everywhere

The last notable not-so-pleasant side effect that I started experiencing near the end of my carnivore experiment, and one that led me to eventually slowly look for other solutions, was when I started experiencing leg cramps (also known as Charley horses) in my calves upon waking up. Although I was terrified of adding different foods into my dietary regimen and aggravating my digestion again, the leg cramps were pretty horrible too, so it was time to make some changes.

I attribute the cramping to the electrolyte-wasting effect of low-carb diets. First of all, the carnivore diet can be quite low in potassium and magnesium. Second, cortisol and other stress hormones, expedite the loss of potassium33 and magnesium34 from the body. Third, insulin (the oh-so-feared insulin in the keto world) actually stimulates the uptake of magnesium35 and potassium36 by cells. And although meat itself can cause an elevation in insulin, it is not as insulinogenic as carbohydrates. By lowering insulin, low-carb diets reduce the body’s ability to absorb important minerals. Lastly, as mentioned earlier, running on fat causes cells to become hypoxic (because less CO2 is produced) which will lower ATP. Low ATP, just like low magnesium, can lead to cramping.37

Anyway, it was time to look for answers again, and thankfully I eventually found the work of Dr. Raymond Peat who does an incredible job in connecting the dots and presenting “medical archeology,” bringing light to long-forgotten and extremely enlightening research. Through his work (and the work of other brilliant minds that I discovered thanks to him) I was able to finally start piecing together the full picture of what causes thyroid function to deteriorate, and while I realized that I was already on the right track avoiding vegetable oils since my Paleo days and avoiding plant toxins and gut irritants starting in my carnivore days, I really missed the mark with the whole low-carb fiasco. It was time to admit that I was wrong and say “sorry” to sugars.

Where I’m at now

I departed from the carnivore diet a bit over 3 years ago now.

In a way I have gone full circle, eating in a way that is a lot more similar to the traditional diet of my grandparents than all the diets that I’ve done in the past. Except I use butter for cooking (as opposed to my family’s beloved atrocity which is canola oil) and I am a lot more particular about sourcing high-quality ingredients without additives.

I still believe that forcing ourselves to eat anything that we don’t enjoy against the warnings of our senses is stupid and shouldn’t be done. I am also still convinced that many raw vegetables can be somewhat toxic to humans and negatively affect thyroid function and gut health, especially those that we find foul tasting (which will differ from person to person). That being said, I am not as gung-ho about avoiding vegetables as I was in my carnivore days, and I use them mainly to add flavour to my cooking. I also made friends with the occasional pickled vegetables again, as I have always enjoyed ferments quite a bit. (It did take my digestion a couple of years to start tolerating them though). I also believe that many of the compounds in vegetables can have certain medicinal, health-promoting effects in certain individuals and that our cravings for certain vegetables can show us which ones we might need.

My digestion has improved to a degree where nowadays I actually find myself craving some greens once in a while (especially in the summer). This supports my hypothesis that the body will repel us from foods that it knows it’ll struggle to digest (which might also be why, inversely, those with low stomach acid can find themselves being repelled from animal products).

My current mode of eating is still quite “meaty,” consisting of organs, shellfish, white fish, chicken, game meat and beef (mostly). However, I have also become fond of having more gelatinous meats, goulashes and soups in my diet (something that I neglected in my carnivore days). I also consume quite a bit of dairy (both raw and pasteurized), actually far more than I do meat. No issues so far.

The biggest departure from my carnivore experiment is that my diet now is actually quite high in carbs and moderate in fat. After learning that sugar in fact does not give you cancer or diabetes (future article topics), I’ve been enjoying plenty of fruit, juice, rice, honey, white sugar and pasta in my diet – all of these being carb sources that I personally digest with ease. And yes, I have grains and gluten back in my diet, although I make sure that the gluten is only from ancient, organic grains (I’ll write about why this matters in the future). I don’t experience any negative digestive effects from grains, and I digest them much more easily than I do most vegetables.

In terms of my stance on plants – fruit deserves a massive apology. I demonized it both in my Paleo days and in my carnivore days but I have now come to realize that fruit might be one of the most perfect foods for humans, and I indulge in it to no limit. Also, ripe fruit contains virtually no plant toxins as fruit actually wants to be eaten.

I still limit fibre intake in my diet as excess endotoxin and bacterial overgrowth are no joke. Most of the fibre in my diet comes from the occasional mushrooms, raw carrots, or the pulp in my orange juice. However, my persisting low dietary fibre consumption has shown me that it is in fact thyroid function that is the biggest driver of bowel frequency, as (even on certain days when I end up eating close to 0 fibre), the lack of dietary fibre does not get in the way of my 2-3 poops-a-day, especially now that my thyroid function is in a much better place than ever before – thanks, carbs!

Do I think the carnivore diet is ever beneficial?

Here’s the thing - I am extremely grateful for the relief from digestive issues that this diet provided me with and that it showed me what it’s like to have painless digestion. I empathize deeply with anyone turning to the carnivore diet as the last resort for their digestive issues. The carnivore diet is the ultimate elimination diet, and it can help us eliminate any potential intestinal irritants, the removal of which can have profound effects on our health.

That being said, I believe that any short-term benefits of the carnivore diet will be far offset by the consequences of going low or zero-carb.

I think that anyone turning to the carnivore way of eating should try and include at least some carbs in their diet, whatever it is that agrees with their digestion, whether it be white rice, potatoes, oatmeal, honey, strained juice, or even white sugar, with added coconut water for potassium. This is something that I personally wish I would have done.

Ironically, long-term carnivore diets actually tend to bring on the very gut issues that they initially bring relief for. Over time, slower gut motility due to decreased T3 can increase the absorption of gut toxins and bacterial proliferation.

I’m of the belief that having the ability to eat some properly prepared, cooked or fermented vegetables is an ability that we earn as our gut health improves, as opposed to being something that can improve the gut health of someone in an extremely compromised position. Limiting the intake of hard-to-digest fibres is helpful, and I stand by that. But we can’t keep indefinitely completely eliminating all plant foods and carbohydrates from our diets without some consequences. Instead, we should focus on solving the very metabolic issues that can slow our gut motility and lead to bacterial overgrowth. By focusing on supporting the body’s ability to produce and utilize thyroid hormones (by eating adequate calories, not skipping meals, limiting our intake of polyunsaturated fats, avoiding hard-to-digest foods, eating nutrient-dense animal products and simple carbs, and limiting stressors in our lives), we can address the root cause behind many gut issues and make ourselves more resilient, to handle many more foods in the future.

Why I am extremely grateful for my carnivore experiment

Although my carnivore experiment did not end in the most positive of ways, I could not be more grateful for it. Namely because:

It taught me that most conventional “superfoods,” like green smoothies or chia seeds are a complete scam (a statement that I stand by to this day).

It proved to me that I should trust my senses more, especially if what they are telling me is not in alignment with whatever the nutritional dogma of the current season is.

It got me to question my preconceived notions and what I thought I knew about nutrition, and to keep an open mind to other “crazy” dietary ideas, which is how I’ve arrived at many of the ideas that I hold now.

Its failure taught me how to really question and investigate nutritional claims by trying to truly understand the mechanisms behind how something works as opposed to taking an “expert’s” word for it.

Another aspect of the carnivore diet that I am grateful for is that the various rabbit holes through which it sent me, got me to introduce raw animal products into my diet (more on that in another article).

Anyway, I hope you found this at least somewhat insightful and entertaining. Thank you for the time spent reading this and stay tuned for part 2 of this article where I will talk about my experience with the raw carnivore diet (as talking about it here would make this already obnoxiously long article far too long).

Disclaimer: The information contained in this article is for educational and entertainment purposes only. It is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice and should not be relied on as health or personal advice. Always seek the guidance of your doctor or other qualified health professionals with any questions you may have regarding your health or medical condition.

Kip Panter, USDA-ARS Poisonous Plant Research Laboratory, Logan, UT, Beef Magazine, May 15, 2019, “Fact Sheet: Poisonous Plants.” https://www.beefmagazine.com/pasture-range/0505-fact-sheet-poisonous-plants

Evan Wright & D. P. Sinclair (1958), “The goitrogenic effect of thousand-headed kale on adult sheep and rabbits, New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research,” https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/00288233.1958.10431532

Bajaj JK, Salwan P, Salwan S. “Various Possible Toxicants Involved in Thyroid Dysfunction: A Review.” J Clin Diagn Res. 2016 Jan;10(1):FE01-3. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/15195.7092.

Mancini A, Di Segni C, Raimondo S, Olivieri G, Silvestrini A, Meucci E, Currò D. “Thyroid Hormones, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation.” Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:6757154. doi: 10.1155/2016/6757154.

Science Direct, “Endotoxin,” https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/endotoxin

Myhrstad MCW, Tunsjø H, Charnock C, Telle-Hansen VH. Dietary Fiber, Gut Microbiota, and Metabolic Regulation-Current Status in Human Randomized Trials. Nutrients. 2020 Mar 23;12(3):859. doi: 10.3390/nu12030859

Science Direct, “Endotoxin,” https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/endotoxin

Peeters RP, Visser TJ. “Metabolism of Thyroid Hormone.” [Updated 2017 Jan 1]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000

W. J. Penhale & P. R. Young, “The influence of the normal microbial flora on the susceptibility of rats to experimental autoimmune thyroiditis,” School of Veterinary Studies, Murdoch University, Murdoch, Western Australia, 1988

Bánhegyi G, Mucha I, Garzó T, Antoni F, Mandl J. “Endotoxin inhibits glucuronidation in the liver. An effect mediated by intercellular communication.” Biochem Pharmacol. 1995 Jan 6;49(1):65-8. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)00389-4

McGivney A, Bradley SG. Action of bacterial endotoxin and lipid A on mitochondrial enzyme activities of cells in culture and subcellular fractions. Infect Immun. 1979 Aug;25(2):664-71. doi: 10.1128/iai.25.2.664-671.1979

Sayyah M, Eslami K, AlaiShehni S, Kouti L. Cognitive Function before and during Treatment with Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors in Patients with Depression or Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Psychiatry J. 2016;2016:5480391. doi: 10.1155/2016/5480391.

Luckey TD, Reyniers JA, Gyorgy P, Forbes M. “Germfree animals and liver necrosis.” Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1954 May 10;57(6):932-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1954.tb36472.x.

Broitman SA, Gottlieb LS, Zamcheck N. “Influence of Neomycin and ingested endotoxin in the pathogenesis of choline deficiency cirrhosis in the adult rat.” J Exp Med. 1964 Apr 1;119(4):633-42. doi: 10.1084/jem.119.4.633. PMID: 14151103;

“Gut serotonin (due to bacteria) is the master regulator of metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and weight,” www.haidut.me, September 18, 2019

Gaskins AJ, Mumford SL, Zhang C, Wactawski-Wende J, Hovey KM, Whitcomb BW, Howards PP, Perkins NJ, Yeung E, Schisterman EF; BioCycle Study Group. “Effect of daily fiber intake on reproductive function: the BioCycle Study.” Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Oct;90(4):1061-9. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.27990

Peat, Raymond, Ph.D., “Milk in context: Allergies, ecology, and some myths,” Ray Peat’s Newsletter, July 2010

Peat, Raymond, Ph.D., “Phosphate, activation, ageing,” 2013

Kemi VE, Kärkkäinen MU, Lamberg-Allardt CJ. High phosphorus intakes acutely and negatively affect Ca and bone metabolism in a dose-dependent manner in healthy young females. Br J Nutr. 2006 Sep;96(3):545-52. PMID: 16925861.

Kirchner S, Muduli A, Casirola D, Prum K, Douard V, Ferraris RP. Luminal fructose inhibits rat intestinal sodium-phosphate cotransporter gene expression and phosphate uptake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008 Apr;87(4):1028-38. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.4.1028. PMID: 18400728

Peat, Raymond, Ph.D., “Phosphate, activation, ageing,” 2013

Jean-Pierre Vilardaga, Peter A. Friedman, “Molecular Biology of Parathyroid Hormone,” Textbook of Nephro-Endocrinology (Second Edition), 2018

Schönfeld P, Reiser G. “Why does brain metabolism not favor burning of fatty acids to provide energy? Reflections on disadvantages of the use of free fatty acids as fuel for brain.” J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2013 Oct;33(10):1493-9. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.128. Epub 2013 Aug 7. PMID: 23921897

Wheaton WW, Chandel NS. Hypoxia. 2. “Hypoxia regulates cellular metabolism.” Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011 Mar;300(3):C385-93. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00485.2010. Epub 2010 Dec 1. PMID: 21123733

Sendoel A, Hengartner MO. “Apoptotic cell death under hypoxia.” Physiology (Bethesda). 2014 May;29(3):168-76. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00016.2013

Peat, Raymond, Ph.D., “Phosphate, activation, ageing,” 2013

Canzanello VJ, Kraut JA, Holick MF, Johns C, Liu CC, Madias NE. “Effect of chronic respiratory acidosis on calcium metabolism in the rat.” J Lab Clin Med. 1995 Jul;126(1):81-7

Iacovides S, Maloney SK, Bhana S, Angamia Z, Meiring RM. “Could the ketogenic diet induce a shift in thyroid function and support a metabolic advantage in healthy participants? A pilot randomized-controlled-crossover trial.” PLoS One. 2022 Jun 3;17(6):e0269440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0269440.

Nauman A, Kamiński T, Herbaczyńska-Cedro K. “In vivo and in vitro effects of adrenaline on conversion of thyroxine to triiodothyronine and to reverse-triiodothyronine in dog liver and heart.” Eur J Clin Invest. 1980 Jun;10(3):189-92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1980.tb00019.x. PMID: 6783414

Kabadi UM, Premachandra BN. “Glucagon administration induces lowering of serum T3 and rise in reverse T3 in euthyroid healthy subjects.” Horm Metab Res. 1985 Dec;17(12):667-70. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1013639

Heyma P, Larkins RG. “Glucocorticoids decrease in conversion of thyroxine into 3, 5, 3'-tri-iodothyronine by isolated rat renal tubules.” Clin Sci (Lond). 1982 Feb;62(2):215-20. doi: 10.1042/cs0620215. PMID: 7053919.

K. R. Short, J. Nygren, R. Barazzoni, J. Levine, K. S. Nair, “T3 increases mitochondrial ATP production in oxidative muscle despite increased expression of UCP2 and -3,” American Journal of Physiology, Endocrinology and Metabolism, 2001 May 01, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.2001.280.5.E761

McKay LI, Cidlowski JA. “Physiologic and Pharmacologic Effects of Corticosteroids.” In: Kufe DW, Pollock RE, Weichselbaum RR, et al., editors. Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine. 6th edition. Hamilton (ON): BC Decker; 2003.

Ryzen E, Servis KL, Rude RK. “Effect of intravenous epinephrine on serum magnesium and free intracellular red blood cell magnesium concentrations measured by nuclear magnetic resonance.” J Am Coll Nutr. 1990 Apr;9(2):114-9. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1990.10720359.

Takaya J, Higashino H, Kobayashi Y. “Intracellular magnesium and insulin resistance.” Magnes Res. 2004 Jun;17(2):126-36.

Nguyen TQ, Maalouf NM, Sakhaee K, Moe OW. “Comparison of insulin action on glucose versus potassium uptake in humans.” Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011 Jul;6(7):1533-9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00750111.

Peat, Raymond, Ph.D., “Phosphate, activation, ageing,” 2013

Haha I love this sentence - If this state becomes chronic (such as when choosing to stay alive when eating zero carbs) 😂

Such interesting info Kaya! Especially about high cholesterol actually indicating low thyroid. Makes a lot of sense for my family.

This is really great reading. Looking forward to more :)